George VI, father of recently deceased Queen Elizabeth II, was apparently the first member of the British royal family to refer to the Windsors not as a family, but as a firm. The irony is that today, I’d bet they wish they actually were one.

Alas, they are in fact a family. And so the question arises: what are the likely consequences for the House of Windsor, now that the person formerly-known-as-Prince, Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor has been arrested in a criminal case this week?

If they were in fact a firm, you can imagine what would be happening in the boardroom. Everyone would be summoned to a crisis meeting to establish a 'war room' and would be using the word “pivot” every five or six milliseconds. The public relations consultant, now known as The Office of Institutional Integrity, would be forced to deliver the grim news:

“The recent legal entanglements involving former executives (specifically the "Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor" matter) have exposed critical vulnerabilities in our operational risk management. To ensure the long-term viability of the brand, we must move beyond the "Family Business" optics and embrace a "Public Trust Corporation" model.

A new “Governance Framework” would be proposed. Concretely, this would consist of the "Crown Oversight Board" (COB). Some “slimming down” would be necessary, following which the COB would establish a transparent “Code of Conduct” (COC). Any member found in breach of the COC, say by having sex with underage girls, would trigger the "de-listing" process, in which they would strip titles and funding.

This would be considerably more preferable to the current process, in which “de-listing” (removing Mr Windsor-Mountbatten as the eighth in line for succession to the throne) would require consultation with not only the British parliament, but the 14 countries where the British monarch is currently the ceremonial head of state. I am not making this up.

It's tempting to think that the arrest of Windsor-Mountbatten will ultimately have little effect on the British Royal Family. I was a correspondent for a SA newspaper (Business Day) when King Charles’s then-wife, Diana, was killed in a car accident in Paris. Diana's separation from her husband beforehand was the subject of almost constant attention and gossip.

One of my favourite writers at the time, Julie Burchill, wrote in the Guardian perhaps the most excoriating, funny, sad, and angry piece about the incident. “We have seen Diana the Good, Diana the Stylish, Diana the Dutiful. These were, of course, real and valid Dianas. But we have not yet seen the other great Diana - Diana the Destroyer. And destroyer she has been, gloriously so, with bells on the greatest force for republicanism since Oliver Cromwell.”

“Diana showed the House of Windsor up for what it was: a dumb, numb dinosaur, lumbering along in a world of its own, gorged sick on arrogance and ignorance. Above all, she showed up her husband, the supposed 'intellectual' of the Firm, for what he was: a third-rate mind with delusions of adequacy, a veritable human jukebox of philosophical cliches completely unable to concentrate or contribute to any cause for any length of time,” the piece said.

Burchill concluded with what was effectively a call for republicanism: “Her brave, bright, brash life will forever cast a giant shadow over the sickly bunch of bullies who call themselves our ruling house. We'll always remember her, coming home for the last time to us, free at last, the People's Princess, not the Windsors'. We'll never forget her. And neither will they”.

But you know what: we did kinda forget Diana (and so did they, faster, I presume) except as fodder for television dramas. I remember writing at the time that I didn’t think Diana’s demise was a death-knell for the royal family - in a way, it was the opposite. It removed a visible, enduring critic and allowed the family to gradually regain their stature.

The family had, after all, not done anything specifically wrong; they were not responsible for Diana flashing around with a new boyfriend in Paris. And marriages go wrong all the time. The Queen, particularly, was seen as above it all, stoic and understanding. They might have treated Diana badly, but for royalists, it could be argued at a push that she treated them badly too by being disloyal and frivolous.

As for Mr Windsor-Mountbatten, there is actually no real chance he will ever actually become king. The British system of absolute primogeniture prioritises direct descendants before moving to siblings or collateral lines. So if Prince William’s kids have kids of their own, they will shift Andrew even further down the line.

So, all in all, it's tempting to think the arrest of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor following the revelations in the Epstein Files will have no real consequences for the broader royal family. The British monarchy has survived wars, divorces, abdications, tampon scandals, a Windsor Castle fire, and the occasional interview that looks like a hostage video. It is also perfectly possible that the practical consequences will be much smaller than the moral drama suggests.

That said, the facts in this case are extraordinary and now hanging over Buckingham Palace like a damp ermine robe.

Windsor-Mountbatten was arrested by Thames Valley Police on suspicion of misconduct in public office, questioned, and released under investigation, while searches were carried out at properties linked to him. King Charles publicly said, “The law must take its course,” and backed the process. The Guardian reports the palace was not warned in advance and that police searches continued after the arrest.

The monarchy’s central strategy will now be to continue to try and isolate the problem by keeping the focus on Andrew; they have already spent years quarantining him. He ceased to be a working royal in 2019; paid a reported £12m settlement in 2022 to Virginia Giuffre without admission of liability, has since been stripped of titles and duties and even been booted out of his family residence. The family has been trying, in institutional terms, to turn him from a blood-relative problem into a footnote.

Institutions survive scandal by narrowing the perimeter. If Andrew is no longer a working royal, no longer publicly front-and-centre, and increasingly treated as a constitutional anomaly to be legislated around, then the palace can plausibly argue that this is a criminal matter concerning one man, not the monarchy’s core operating model.

The modern monarchy is no longer sold primarily as a medieval household but as a constitutional service brand. This is essentially what King George VI was talking about when he described the effort as a “Firm, not a family”. The royal family is essentially an institution now, and its members are part of a public-facing operation with roles, duties and protocols.

This is why the Royal Household’s own financial summary for 2024–25 leans heavily into this 'service' framing: 1,900+ engagements, 828 events at official palaces, and the language of value-for-money, maintenance, sustainability, and visitors. The Sovereign Grant remained flat at £86.3m, supplemented by £21.5m in additional income.

Support for the monarchy hovers around 60–70% in polls; Charles and William remain popular - but the longer term trend is down. The Firm's core product—pageantry, continuity, tourism—chugs along. And up till now, republicans crow, but abolition has remained a fringe hobby.

But - and is a big but - in this case, I think the problem for the firm is bigger now than it might appear from history. The monarchy is, at heart, a reputational machine. It survives because millions of people consent that continuity, duty, restraint, family, and service. Andrew’s saga attacks each of those emblems.

And the latest development is different from mere embarrassment. This is not a ghastly interview, nor another tabloid revelation, nor a gossip-column inferno. It is arrest, police process, searches, and the possibility, however distant, of a criminal charge. Even if the legal case never lands, the image has already done so: a senior royal by birth, brother of the King, taken in for questioning over alleged misconduct tied to Epstein-era allegations. That image is constitutional acid.

Much depends on the actual charge and how it pans out. The reported suspected offence is misconduct in public office (MiPO), a common-law offence in England and Wales. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) holds that it is indictable-only, carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, and concerns serious wilful abuse or neglect of the powers or responsibilities of a public office, with a direct link between the misconduct and those powers.

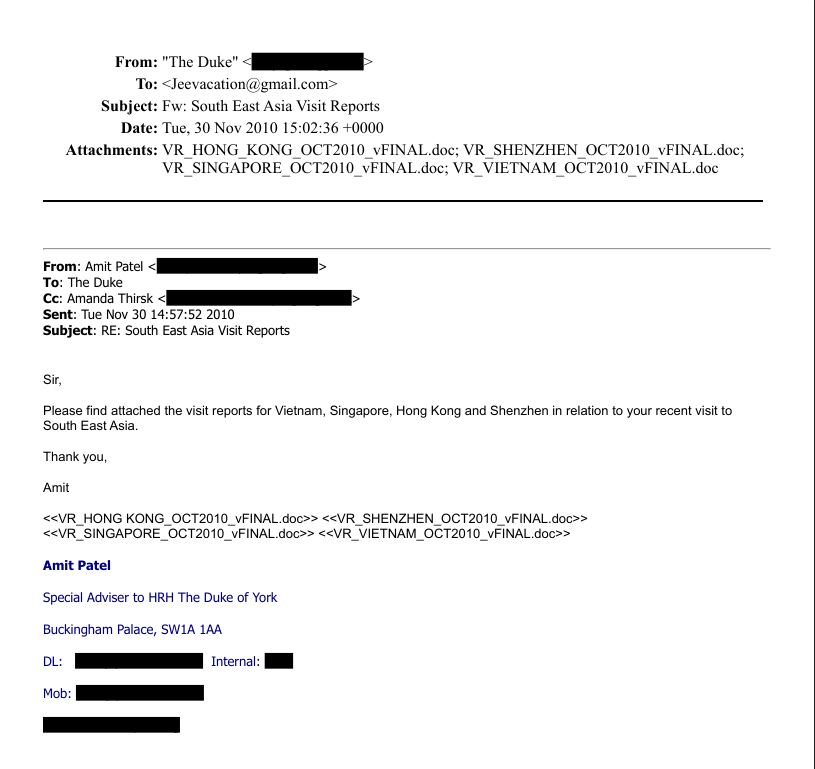

The offence is intentionally narrow, and both the CPS and Law Commission have in the past noted its complexity; the Law Commission has long criticised MiPO as ill-defined and recommended statutory replacement, with the government having introduced new offences in a 2025 bill building on those recommendations. And as always, the difficulties of proof will be substantial. The case apparently involves, at least partly, this email.

The email was forwarded to Epstein less than five minutes after the then-Prince received it from his private secretary at the time, Amit Patel. What it suggests is that Mountbatten-Windsor leaked trade envoy reports, coming out in the context of other leaks involving the recently sacked British Ambassador to the US, Lord Mandelson, who allegedly passed market-sensitive information while a minister.

Together, it suggests Epstein was very interested in market-sensitive information. So what did these four reports contain? We don’t know: the contents weren’t revealed when the US Department of Justice posted the emails.

But normally, they would probably not have been particularly sensitive, although emails suggest other occasions when Mountbatten-Windsor actively promoted Epstein when he was acting as a UK global trade envoy.

There have been around 50 prosecutions a year under the law, and around 20 convictions a year. If Windsor-Mountbatten is charged and found guilty, obviously, the consequences would be profound even if the sentence were far below the theoretical maximum. For the monarchy, it will entrench the idea that its internal controls failed catastrophically around one of its most prominent members. And for the family, that rather sadly will include the much-loved and now deceased Queen Elizabeth. Andrew was the favourite son, whom she fiercely protected, and consequently, all in the royal household were loath to bring his laxity to her notice. If the firm were a firm, that might not have been the case.

Andrew’s arrest may prove, in strictly legal terms, to mean little. It may end in no charge, or an acquittal, or a long, unsatisfactory procedural fog. But even in the best scenario, the charge means years of drip-drip-drip bad publicity for an organisation founded on public approval.

It's likely to show that the monarchy’s oldest vulnerability remains the same as ever — not republicanism, not Netflix, not modernity, but kinship without governance.

And for a family that survives by looking eternal, that is the one thing it can least afford. 💥

From the department of cheating cheaters caught cheating ...

From the department of another movie franchise is born ...

From the department of how far is eight billion light-years anyway?

From the department of we are all in favour of transparency, but really ...

Thanks for reading - please share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation