I’ve written a few times now for Currency (my day job) about the song Waka Waka, which, honestly, I think is an egregious international travesty involving —almost by contractual obligation — two of the most notorious organisations out there: soccer federation Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) and the global music industry powerhouse Sony Music. But crucial questions remain unanswered, largely because nobody involved appears to answer questions.

It's a fascinating story, so indulge me, if you please. I’m looking for a way forward.

First, some background. The little desert town in which I stay, Prince Albert, includes some truly eccentric, wonderful people, as desert towns often do. One of those people is Simon Attwell, a flautist cum banjo player (I am not making this up), who is a member of the band Freshlyground and of a newer group called the Congo Cowboys. Simon’s father used to live in the town, and he uses that house as an occasional refuge from the crazy world of international pop music for Attwell and his family. (Freshlyground BTW have a new album coming out, and have released a song teaser Jabula.)

Even among the extraordinary assortment of professional musicians out there, Simon is unusual. A sometimes pilot, mountain climber, and now, would you believe, MBA student, he is tall, wiry and has a very sympathetic and unassuming personality, especially for someone who has been involved in a pop band for so long and so successfully.

Because it's a small town, you bump into people regularly, and I’ve got to know Simon and his powerhouse wife, who has her hands in as many pies as he does. One day, he told me the Waka Waka story, and I offered to write something about it; Simon cautiously agreed.

The story is basically this: The song is the most commercially successful song involving South African musicians. Simply put, it's the country's biggest individual musical export. By a long shot. What about When the Lion Sleeps Tonight you ask? Doesn't touch it. What about Weekend Special, Pata Pata, Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes, Qongqothwane (the Click Song) and dozens of other songs involving South African music and musicians? Nothing comes close. The nearest is Master KG’s Jerusalema but even that song has only a fraction of the streams on Spotify and views on YouTube that Waka Waka has, although it is, of course, a wholly local production.

Waka Waka was, as we all know, produced for the South African 2010 soccer World Cup. It became a number one hit in 21 countries, it has over four and a half billion YouTube views and over a billion streams on Spotify alone. That’s a lotta zeros. It's the seventh most-viewed song on YouTube of all time. What adds so much to the chronicle is that its popularity has been so enduring; it had more views on YouTube in 2022 than it did in the year of its release.

And its unexpected longevity is part of the problem.

The biggest irony may be that neither Colombian pop artist Shakira, who is the featured singer and who has an unlikely co-writing credit, nor the band members of Freshlyground, expected the song to last beyond the year of its release. They didn’t even expect it to do particularly well in that year. You can tell this because they signed away the rights to the master copy of the song. Big mistake.

But isn’t this just part of the story of so much popular music? Nobody knows how things are going to turn out. Something just clicked with Waka Waka; at every soccer World Cup, it returns and hits the charts again. People just love it, and the music video linked to it, featuring Messi and Renaldo, partly I think because it's not embarrassingly contingent on the tournament or even soccer itself. It's just a joyful and catchy tune.

The reason the musicians thought it wouldn’t last is that until Waka Waka, World Cup songs never had. They were always too associated with the event, and consequently faded away as the event left people’s consciousness. Even great songs by great artists, like the Cup of Life, the official song of the 1998 World Cup in France, which features Ricky Martin, has only 46 million views on YouTube.

World Cup songs normally just don’t cut it in the pop world: they are too linked to a sporting event and therefore, too uncool, too programmatic, and faintly redolent of corporate PowerPoint. Waka Waka, however, laid the foundation for a recurring set of official World Cup songs that have done well on the pop charts, rather like what Diamonds are Forever did for Bond movie theme songs.

The other way you can tell people didn’t give much of a thought to the future importance of the song is because the originally credited writers, Shakira and Shakira’s regular songwriting partner John Hill, er, how do we phrase this, appropriated it. Shakira notoriously offered a version of events that was, let’s say, more pastoral than accurate, saying she got the whole verse and chorus in an instant while walking from a barn as she was taking a break on her farm in Columbia. She said she ran into the house and shouted, “I’ve got it, I’ve got it.” Actually, she didn’t.

In truth, Hill found the song while trawling through African music looking for inspiration because Sony Music had asked him to work on a song for the Cup. The original song is Tamina Mina, written and performed in the mid-80s by the Makossa band Golden Sounds (Zangaléwa), a group of Cameroonian soldiers and musicians.

Here is the original song,

Here is the final version.

As you can hear, the chorus is pretty much identical and includes lyrics which are a mixture of the Cameroonian languages Fang and Douala and Cameroonian Pidgin English. When the song came out, it became increasingly obvious that it was, um, poached, because Africans pointed out that little issue en mass.

So, by agreement (by which I mean money was dished out) with the actual writers and producers of the original, the issue was smoothed over very quickly. Members of the Cameroonian group Golden Sounds/Zangalewa, Guy Dooh, Jean Paul Ze Bella, and their manager Didier Edo, held a press conference at the time, and Edo said: "There is no question of plagiarism as some have thought, but the international singer has simply readapted the song", and that there was an agreement with Shakira's management and Sony Music. Phew!

What Shakira and Hill did do, which was truly inspired, was to add to the lyric “Zamina mina, zangalewa? the words “this time for Africa”. The original lyric Come, come, where do you come from? was meant as a kind of taunt to marching soldiers). But the addition of "this time for Africa" and lyrics of the verse fitted perfectly with the idea of the 2010 World Cup as Africa’s opportunity to claim part of the global soccer movement, particularly since it was the first time the event was being held on the continent.

And then there was the Freshlyground bit, which introduced some kwela into the Cameroonian/Central African Kwassa Kwassa guitar style. Zolani Mahola (Freshlyground’s lead singer at the time) sang her verse mostly in isiXhosa. How did that come about?

Attwell says Freshlyground, who were also signed to Sony Music at the time, happened to be recording their studio album, Radio Africa, in New York. Hill, who happened to be working in the same building at the time, heard there was an African band in the building, and, desperate for some African link, approached them for input on the song. He played them the song as sung by Shakira, and there and then, the band put together a take of the song, including a lively bridge.

Hill came back a few hours later to listen to it. Attwell says he didn’t say much at the time, but expressed interest and said they would hear from him later. They didn’t. The first time the band knew they were part of the song was when Sony Music informed them a week or so before the song's release. The first time they heard the final version was on the radio.

But the band did hear from Sony Music management before that. Attwell says Sony and the managers of the bands agreed at the time that the proceeds of the song should go to charity. Consequently, on April 6, 2010, Attwell got an email from Sony Music representative Stephanie Yu, which put this idea in writing. The crucial part of the email says this:

“Sony Music Entertainment (“SME”) has been selected by FIFA to create the official music for the upcoming 2010 World Cup in South Africa. In connection therewith, SME plans to release an Official Song which will be sold as a single (the “Single”) and as part of a multi-artist compilation album featuring recording artists from around the world (the “Official Album”). All net profits from sales of the Single and Official Album will be donated to African charities selected by the participating artists. Set forth below is our proposal for the use of “Time for Africa” (the “Master”) featuring the performance of Shakira and the side artist performance of Freshlyground (“Artist”) as the Official Song.

Grant of Rights: All rights in the Master, including, without limitation, the worldwide copyright, will be owned by SME in perpetuity. SME shall have the worldwide right, in perpetuity, to use (and to authorize the use of) the Master and underlying composition for exploitation in any media now known or hereafter devised, and in related trailers, featurettes, advertising, promotions, and co-promotions, in any and all media (collectively, the “Promotions”), as well as the right to use Artist’s name and approved likeness in connection with the Promotions.

Costs: SME will be responsible for the recording costs incurred in the creation of the Master pursuant to an approved budget.

Royalty: Gratis

Mechanical Royalty: Artist will grant, or cause their publisher to grant, a gratis publishing license.”

Actually, as it turns out, both the Cameroonian songwriters and Freshyground do get a very small publishing fee, which they had to fight for. Shakira and Hill, on the other hand, got a big slice of the publishing fees, which over the years has amounted to millions in income. That is a little ironic for a song supposed to fund charities. A big slice of the income came from the master copy, and that accrued to Sony Music, which (Sony claims) it passed on to FIFA as agreed, which then helped to fund something called the 20 Centres for 2010 Campaign.

But at the time of the release of the song, everyone seemed pretty happy with the arrangement. The song got caught up in the 2010 spirit; the song was a grand hit, and the money is going to charity. What could possibly be wrong with that?

The trouble comes with the phrase “All net profits from sales of the Single and Official Album will be donated to African charities selected by the participating artists”. Attwell says the band was never asked who they wanted to benefit, but at the time, everyone was pretty relaxed about it, because the song probably wasn't going to amount to much, and FIFA had it in hand.

But as the years rolled by, Attwell started worrying about it, because the song was continuing to rack up income. So where was it going? The 20 Centres for 2010 Campaign was never officially wound up, but it kinda faded out. FIFA had a big crisis involving bribery and stuff, as we all remember, and there was a big change in management and operations. Clearly trying to mollify public opinion, FIFA started something called the FIFA Foundation, which took over the organisation’s charity work. But the undertaking that the band would have a say in who should benefit was never honoured, at least in respect of Freshlyground.

So over the years, Attwell asked Sony Music what was going on, and was repeatedly given the heave-ho. On numerous occasions, he would ask Sony Music to give him a breakdown of the song's earnings and how much was being donated to FIFA. The email responses border on the wryly amusing; difficulties in contacting New York was one excuse. And then, simply no response.

It was at this point, I think with some frustration, that Attwell complained to me (a journalist) about what was happening, implicitly allowing the issue to go public. So I contacted Sony Music (and joined the now long list of people being ignored). I also approached FIFA, who - surprise! - also ignored me. I sent FIFA another email asking for an earnings breakdown, and was ignored. I then asked FIFA if they were just prepared to acknowledge receipt of my email. They did! Hallelujah.

A small miracle, though not a useful one, since they didn’t break down the income. So somewhat in frustration, Currency decided to publish the story as we had it so far, just to record the broad circumstances and the band’s complaint.

After this, there was a bit of a media flurry. There were stories all over the place, many in South Africa, but also in Spain and the UK (none of which acknowledged Currency BTW). The best international story came from a sports journalist, Martyn Ziegler from the London Times, then put in a query to FIFA and Sony, and then both organisations jumped into action. What! Shows what happens if you work for a powerful British publication rather than a puny African one.

A Sony Music spokesman promised it had sent all the proceeds from the song to FIFA. “For the past 15 years, Sony Music has paid, and continues to pay, the designated royalties from the official World Cup version of Waka Waka to FIFA, which oversees distribution to the selected charities chosen by the artists on the track.”

Well, this is plainly not true, since Freshlyground were never asked to select a charity.

For its part, FIFA told The Times: “[Our] total investment in the construction of the centres and the support to those organisations has been significantly higher than the revenues received by FIFA as royalties of the FIFA World Cup 2010 soundtrack.”

This is also duplicitous.

FIFA is an international federation of national soccer organisations, and its key event is the World Cup. Consequently, FIFA distributes the proceeds that it earns from the Cup to the six FIFA confederations, without whom it would not exist. The confederations then distribute the money to the national organisations, without whom they would not exist. They use it to support the clubs and their own operations. This is a long-standing arrangement intrinsic to the organisation.

FIFA is also, as it happens, rolling in boodle because the World Cup is a fabulously and increasingly profitable business. FIFA operates on four-year cycles and makes huge profits in World Cup years, which it pays down in non-World Cup years. In the 2010-2014 cycle for example, its turnover was about $5.7-billion and profit (or “surplus” in FIFA’s terminology) was about $338m. Those figures are now about $7.4-billion and $1.3 billion, respectively, according to its annual report.

Consequently, it is hardly surprising that the support for clubs and the various social programs should be higher than the revenues received by FIFA for a single song. The question is what happened to the extra income that FIFA got from the song? Surely that should come on top of what FIFA distributes anyway?

There is one possibility, and that is that although Freshlyground decided to hand over its income from the song to charity, Shakira didn’t. That might explain why the amount FIFA is getting from the song is so low. The Times story says the total here “is thought to be at least £7-million”.

Well, that seems a little light. Industry experts calculate that the earnings of a song with the statistics cited above would be around $40- to $50-million. (Streaming revenue varies wildly by territory, platform and whether it's streamed on a premium site).

But that just enhances the question about how this is all being accounted for. So I asked FIFA once again if they would just send me the statement they had sent The Times, and give me a year-by-year breakdown of what they got and where the money went. They just ignored me again.

Well, they ignored me at least until I tweeted the story and the questions, and this time tagged not only the head of media, but also the CEO of FIFA, Gianni Infantino. So then someone from FIFA phoned me the next day. Fabulous! A human at last. Or at least a convincing simulation.

Actually, no such luck. They did send me the statement. It was three paragraphs long. But no year-by-year breakdown, and crucially, no response to the question of why they never asked the band who they wanted the money to benefit.

To be fair to FIFA, they are supporting, to some extent, 130 non-governmental organisations from across 54 countries through the FIFA Foundation. In addition, I think very few of the existing FIFA staff were around when the original Waka Waka arrangement was established. Four of those are the same organisations established as part of the 20 for 2010 outreach. FIFA is still backing - it doesn’t say to what extent - five organisations in SA: Good Hope Football Club, Training4Changes, United Through Sport, Grassroot Soccer SA, and Special Olympics SA. The FIFA Foundation Advisory Board includes SA tech entrepreneur Robert Gumede. I reached out to him - he ignored me.

I also contacted SA’s Minister of Sport, Arts and Culture, Gayton McKenzie. Here, I thought it would be a great opportunity to show some support for local musicians. He ignored me. Presumably, too busy closing down national arts festivals.

This getting-ignored thing is a syndrome, particularly those from small African publications - one gets used to it. But in this case, I think there is something different at work: FIFA is just from Mars. The organisation has an invulnerability and imperviousness which has allowed it in the past to be so gobsmackingly corrupt and contemptuous of the supporters of the sport it represents. (This was evidenced recently by granting US President Donald Trump, surely one of the world’s most disliked leaders by international soccer supporters, a fake peace prize. I mean, really).

Anyway, I approached the band again and asked if they were satisfied with the response of FIFA and Sony Music. The short answer was “no”.

“We have requested financial statements showing total money received by Sony from Waka Waka, and total money paid over to FIFA/charity … we know how simple it would be for such a breakdown to be generated for Waka Waka and shared with us. That this hasn’t been done so far is puzzling. We have not been given a reason why this has not been provided, nor can we think of a good one. The lack of transparency is concerning, especially given that this was meant to be a charitable endeavour.”

“Whether the agreement was fully executed as originally contemplated, and whether all parties received what the preliminary terms suggested, remains unclear without full financial transparency from Sony and FIFA. Our position is that the charitable intent of the original agreement should be honoured going forward,” the band says.

I think actually it goes a bit further. Since neither Sony Music nor FIFA, with all their masses of resources, can provide a simple breakdown of income and expenditure, I would suggest they have palpably broken a fundamental part of the understanding. So the question is, is there actually a contract at all — or just a very optimistic email, which, it should be noted, describes itself as "a proposal".

It goes even further than that. The original email concluded with the line: “This proposal (my emphasis) remains subject to fully executed contracts and additional internal SME approvals.” That never happened, which just underlines the proposition that there was never a contract. In later emails, Sony Music’s position seems to be that there is a contract, because everybody just operated on the broad basis of the email, so implicitly it was agreed. But this is a legal grey area, surely. It would make a difference, presumably, if Sony Music had actually operated in terms of the email proposal. But they did not.

And there is a bigger issue here: If Sony Music and FIFA cannot demonstrate their claim that they are diligently handing over the proceeds of one of the world's ten most popular songs, how much can other bands and organisations trust them?

I have one proposed solution: shouldn’t the royalties just go to the bands so they can then be responsible for the distribution? The song is obviously not financially relevant to FIFA, or as it happens, to Sony Music because they don’t earn anything from it. (Or at least they claim not to be earning anything from it).

There is another possibility: Why don’t Shakira and Freshlyground simply re-record the song, a la Taylor Swift, and reclaim the master rights that way? If pop stars can wage war on their back catalogues, why not this one? That might be a possibility. Unless, of course, Shakira is already benefitting handsomely from the original.

And there is one other thing: nobody could possibly have known at the time the arrangement was agreed that the song would still be kicking out income fifteen years later. If, as FIFA claims, the income from the song is insignificant to their charity efforts, then why not honour the original agreement and let the bands specify who should benefit? If not, hand the royalties over to the bands who obviously care about it more than they do.

If you have any other suggestions on how this should be taken forward, please send them my way. 💥

From the department of musical wonderment ...

From the department of local is lekker ...

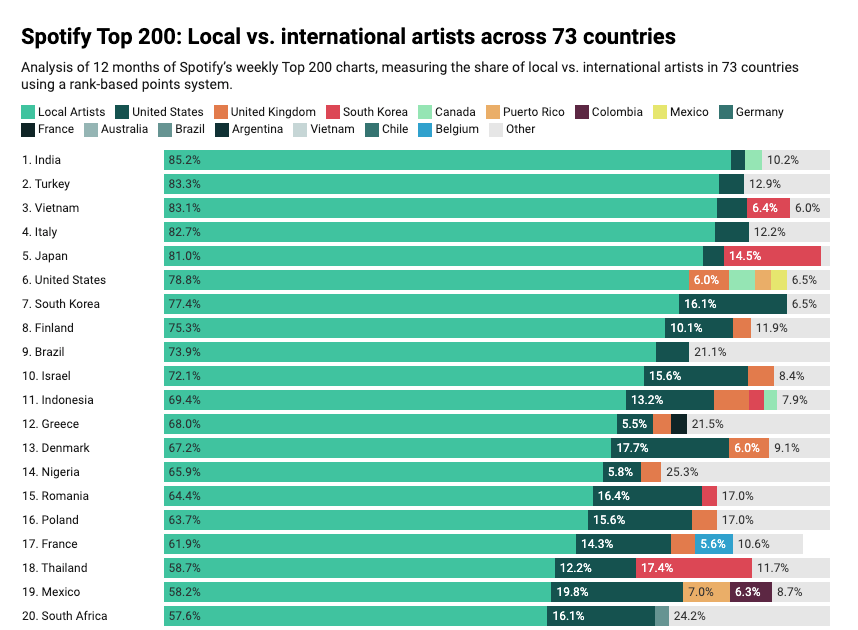

Top 20 ..

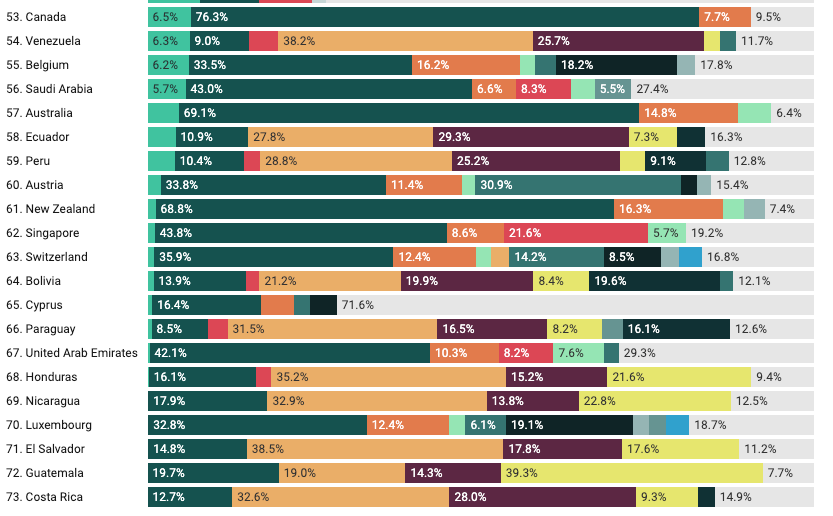

Bottom 20 ..

I can’t believe it, but this blog has now been going for a year. Just to say a big thank you to the 10,000 or so people who are subscribers, and an even bigger thank you to people who are paying the voluntary $20/year contribution.

For the people who signed up and paid for a year’s subscription at the start, that has now lapsed, so you're by all means welcome to donate another cappuccino to me, if you are so inclined!

This blog was conceived as a continuation of the short and humorous After the Bell column I used to write for Daily Maverick. But because I now spend more time working for Currency, I can’t really manage a daily column anymore, so this blog has evolved into quite long columns, often on more serious topics. I trust that's ok with you - the enormous (and extremely pleasing) open-rate suggests readers are getting something out of them (and I’m loving writing them). Let me know if you think the columns are getting too serious or too long - or both! Or not!

Until next time - good investing!

Tim

Join the conversation