This is an chapter extract from my book about the life and legacy of Leon Louw. I wrote the book at the request of friend of Louw's, a South African born US-based businessman Bon Posma. He is a long-time, friend of Leon's, and I should add he financed it, which is very kindly published by Daily Maverick. Anyway, I hope this gives you a taste of the contents of the book, and please do get a copy online or at Amazon or in hard copy at Exclusives. I had a great time interviewing Leon, who life has just been wildly interesting and varied, as this piece shows. We spend a lot of time thinking and talking about where SA should be going and doing if it wants to regain economic growth a prosperity. His ideas are inspiring, fascinating, occasionally controversial, but very convincing. As he often said during the interviews, if my views happen to differ from his, I'm wrong!

“We need millions of property owners, not a handful of millionaires.” – BORIS YELTSIN, 1992

It was a most unlikely setting for the birth of a Siberian economic experiment: a genteel dinner in Johannesburg at the Oppenheimer family residence, Brenthurst, hosted by South African mining magnate Nicky Oppenheimer. Across the table sat Leon Louw and Mikhail Nikolaev, president of far-flung Sakha, the area that most people would think of as Siberia, newly emergent from the rubble of the Soviet Union. It was 1993, roughly two years after that superpower’s collapse, and the conversation over dinner was anything but small talk. Oppenheimer’s company De Beers had its eye on Sakha’s legendary diamond deposits buried deep under Arctic permafrost, and he had brokered this meeting of minds. Oppenheimer asked Louw whether

the Nikolaev administration, which had been elected into the first office of the Sakha Republic in December 1991. Because of his economic strategies, Nikolaev has become a¬able figure in Russian modern politics, serving until 2002. Like in many other regions in Russia at the fall of the Soviet Union, discussions in Sakha were underway to transfer ownership of state-owned entities, which ranged from small mom-and-pop stores to large industrial enterprises, into private hands.

In the case of Sakha (also known as Yakutia), the challenge was enormous. This vast region in north-eastern Siberia had only about 1.1&million people spread across an area as large as India, and it sat atop staggering natural wealth. It was then, and is now, one of the world’s largest producers of diamonds; it also harbours huge reserves of gold, coal, natural gas, and other minerals.

Local folklore captures its mineral bounty in a poetic image: “When the gods were flying over the earth, dropping a few emeralds here and some garnets there, their hands froze over Yakutia and the entire table of elements poured out,” as the Yakuts like to say.10 Beneath the ground lies treasure beyond reckoning, albeit locked under roadless permafrost forests and some of the coldest inhabited lands on the planet. The capital Yakutsk is infamous as the world’s coldest city, where winter temperatures of -50°C are routine. Politically, Sakha in the early 1990s was fexing newfound autonomy in the aftermath of Soviet rule. In the Soviet era, Yakutia had been an “autonomous republic”, nominally self-governing for its predominantly indigenous Yakut (Sakha) people, but in practice tightly controlled by Moscow. With the Soviet collapse in 1991, Sakha rebranded itself with its Yakut name, elected its own president, and asserted a “sovereign republic” status within the new Russian Federation.

Yakutsk: Journey to the coldest city on earth.

Such moves were part of a broader wave of regionalism in postSoviet Russia, a dynamic that both empowered local reform and alarmed the central government. President Boris Yeltsin’s biggest fear, as one Moscow legislator noted, was that Russia itself might unravel into “dozens of fiefdoms” if regions like Sakha pushed too far.11 In 1992, Sakha’s officials successfully demanded a share of their own mineral and precious metal revenues from Moscow, winning the right to a percentage of diamond and gold profits and to conduct their own foreign economic relations to attract investors. In exchange, Sakha pledged to remain within the Russian Federation. Almost overnight, the remote city of Yakutsk saw a parade of foreign businessmen – Australian diamond dealers, Japanese timber merchants, Korean oil executives – arriving to strike deals that previously would have been negotiated solely in Moscow. Even De Beers, the global diamond giant that had a long-standing pact with the Soviet central government, inked a separate contract with the Sakha Republic in the early 1990s. This unprecedented assertiveness by a Russian province made Kremlin o$cials uneasy. Despite this brinkmanship, Sakha’s leaders were savvy enough to know they needed Moscow – and market reforms – as much as Moscow needed Sakha’s bounty. The region’s economy remained largely socialist and stagnant; by late 1992, observers noted that little of the promised “reform” was evident in Yakutia. The old communist power structure was still in charge and “almost all sizable enterprises remain state-owned”.12 Collective farms, state trading companies, and Soviet-era ministries still formed the backbone of daily life.

In short, Sakha had declared the intention to control its destiny but it lacked the economic toolkit to do so. This was the backdrop for Louw’s entry: a province eager to embrace capitalism, yet staffed by officials who had known nothing but communism all their lives. Louw later described the situation with a touch of irony: “These offcials were not about to turn Sakha into some libertarian Singapore overnight; any reforms had to be tailored to their circumstances, their needs, their realities.” The challenge was how to coax a creaking command economy into a more dynamic, decentralised one without triggering backlash from the very bureaucrats and managers who held the levers of power in Sakha’s industries. So as it happens, Louw found himself at Oppenheimer’s request in Russia in 1993 to have a series of conversations with the regional administration, which culminated in a written report. Louw’s counsel in Sakha did not occur in a vacuum.

An unprecedented mass-privatisation campaign was underway across Russia in the early 1990s – an effort to transform a communist economy into a capitalist one virtually at the stroke of a pen. The scale of the endeavour was staggering. Under Soviet communism, private ownership of enterprises had been essentially illegal; virtually everything from steel mills to grocery stores was state property. By one estimate, the Soviet state ran about 45,000 enterprises at the time of its collapse. Starting in 1992, Yeltsin’s reformist government, led by economists like Yegor Gaidar and Anatoly Chubais, set out to transfer the bulk of these assets into private hands in just a few years. It was a highstakes gamble to jump-start a market economy out of socialist ruins, described by some at the time as “the most cataclysmic peacetime economic collapse of an industrial country in history”.

The audacity of the reforms earned nicknames like “shock therapy” and even dark puns such as “katastroika” (a portmanteau of catastrophe and perestroika), redecting the pain and chaos many ordinary Russians experienced during the transition.The centrepiece of Russia’s privatisation was the voucher programme of 1992–1994. Every Russian citizen – all 150 million of them, including children – was issued a paper voucher cheque nominally worth 10,000 rubles, which could be exchanged for shares in state enterprises or sold on an emergent secondary market. The idea, inspired in part by a similar scheme in Czechoslovakia, was boldly egalitarian: “A kind of ticket to the free market economy for each of us,” as Yeltsin proclaimed. “We need millions of property owners, not a handful of millionaires,” he declared,13 articulating a& hope that widespread share ownership would prevent Russia’s wealth from simply falling into the hands of a privileged few. By design, 98% of the population participated, making it one of the largest ownership transfers in history.

In practice, however, the voucher experiment produced outcomes far removed from the idealistic rhetoric. Faced with hyperinfation and economic uncertainty in those post-Soviet years, most people sold their vouchers for quick cash, often for a pittance – the price of a few bottles of vodka or a pair of shoes. One survey in Moscow found over 80% of residents intended to unload their vouchers immediately for rubles, desperate to make ends meet. The predictable result was that “insiders managed to acquire control over most of the assets” being privatised, the survey found. The public’s sense of betrayal grew when they realised that their chance at owning a piece of Russia’s wealth had mostly slipped away into a few crafty pockets. By the mid-1990s, Russia had indeed produced a handful of millionaires – a new class of business oligarchs, precisely what Yeltsin claimed he wanted to avoid.

International Monetary Fund analysis later concluded that the 1990s privatisation led to ownership concentrating among a small number of private individuals, who often raided their companies for personal gain at the expense of the public and the economy. Louw was fully aware of this tumultuous context. His advice to Sakha’s offcials was more cautious and pragmatic, tailored to avoid certain pitfalls. He understood that local bureaucrats and enterprise managers were likely to resist any reform that threatened their positions. These were the people running Sakha’s state-owned mines, bus companies, shops and farms; if privatisation meant they could be replaced or their fiefdoms broken up, they would surely obstruct it. This reality had played out elsewhere: In many Russian regions, the old communist power structure dug in its heels against losing control. Louw categorised privatisation into three broad methods:

1. Dispose of the asset: i.e. sell it off (or even give it away) to new owners.

2. Deregulate and introduce competition: Allow private rivals to compete with (and eventually replace) the state monopoly.

3. Dissolve or close the operation: Simply shut down the state activity if it’s not needed or viable. Each method had its merits. For instance, deregulation was a&form of privatising as it opened the market, which happened when Russia broke Aerofot’s monopoly by letting private airlines fly, or when South Africa ended its state broadcasting monopoly. And some Soviet institutions simply needed to be abolished outright. But in Sakha’s case, the leaders explicitly wanted the “disposal” approach: to hand over ongoing enterprises to private owners rather than just allow competitors or shut them down. The question was, hand them over to whom – and how?

After his initial meetings and fact-finding, Louw formulated a privatisation plan for Sakha that was imbued with a certain dark irony. He often half-joked that the plan essentially involved “bribing those who would otherwise resist” – not with cash in brown envelopes, but with ownership and equity. In blunt terms, give the factory directors and workers themselves a stake – or outright ownership – in the enterprises, so they have no reason to fight against privatisation.

This approach was a twist on the insider buyouts happening elsewhere, but with a crucial difference: It wouldn’t be done surreptitiously or inequitably; it would be the ofcial policy to turn state employees into capitalists. By making managers and staff into shareholders, the reformers could neutralise opposition and align everyone’s incentive towards making the new private business a success. Why protest losing your government job if, suddenly, you are the coowner of the shop or the bus company? Why cling to the communist past if the capitalist future has you profiting as a stakeholder?

Louw recommended the use of employee share ownership plans (ESOPs) and management buyouts across a range of Sakha’s enterprises. In practice, this meant that a state-owned store in Yakutsk might simply be signed over to its store manager and employees in some proportion of shares. A trucking company or a local bus depot could be broken into a few units and similarly distributed to their crews. Even larger operations like hotels or trading firms could be converted to joint-stock companies, where the shares were given, not sold, to the people who already worked there. Louw insists that he cannot claim causality or undue credit. That he proposed something does not imply that it would not otherwise have happened. What he was asked to formulate was not an entirely novel idea; variations of it had been tried in other transitioning economies. Notably, in Czechoslovakia, at about the same time, then-Minister of Finance (later president) Václav Klaus had pioneered mass voucher privatisation in 1992, with some provisions for employee ownership; elsewhere in Eastern Europe, management-employee buyouts were

What Louw proposed was essentially to pre-empt the rise of oligarchs by legally installing the nomenklatura and workforce as the new owners from day one, but doing so equitably at the enterprise level. It was a case of better the devil you know: If the local Soviet-era director was going to grab the factory anyway, better to structure it such that he and his workers formally own it and have responsibility, rather than allowing shadowy speculators from Moscow to swoop in. Louw knew this sounded like rewarding the communists for their past mismanagement, but he argued it was a necessary compromise. In a context where everything was state-owned – from the butcher shops to the bakeries, from mines to hotels – the opposition of even a few dozen mid-level bureaucrats could stall reform indefinitely.

By handing them the keys, reform could proceed. Privatisation by persuasion, one might call it. Louw’s proposals were backed by sound economics. Nobel economist Ronald Coase had formulated the “Coase theorem” according to which it does not matter to whom assets are allocated so long as they are freely tradable. The spontaneous market order will have them transferred into the hands of optimal users. This is why business failure is desirable, as Louw advised Yakut. It is what the Austrian school called “creative destruction”. When governments prop up failed enterprises, such as most of South Africa’s SOEs, they impoverish society by preventing capital from migrating into the hands of maximally efcient users. “I might have come up with a formula and some of the details, but the big picture, the idea, was theirs,” says Louw.

Sakha’s leaders wanted an ownership society, just not one dominated by outsiders. Louw was, in his words, the scribe who helped draft the concrete&steps. What did those steps look like on the ground? In practice, a privatisation commission or working group in Sakha’s government catalogued everything the state owned, a comprehensive inventory from big to small. The list was astonishing in its breadth. Every retail store, every restaurant, every hotel, every repair shop, every farm, every bus company, every mining outfit – literally almost every productive asset was state-owned, no matter how humble or grand. Louw was struck by the sight of Soviet-era butcher shops with o$cial prices posted for cuts of meat, yet with no such meat on the shelves – a classic symptom of a planned economy’s failure.

It was said the Soviet Union was the only place where the price of meat is the price at which the meat is not available – a bit of dark humour that resonated on the streets of Yakutsk, where people joked about the price at which you can’t buy things today. Turning such establishments over to private hands wasn’t just ideological dogma; it was a practical answer to chronic shortages. If the butcher and his staff owned the shop, maybe they’d have the incentive to find suppliers and keep the shelves stocked because their livelihood would depend on it. Sakha’s privatisation emphasised local equity over quick revenue for the government, but there wasn’t a one-size-fits-all approach.

Unlike some privatisations where governments auction off assets to fill the treasury, here the Sakha authorities were, in effect, foregoing immediate financial gain in favour of creating a property-owning class among their citizens. This is why one could cynically call it a “legalised bribe”. Many small businesses were indeed simply transferred to their employees. Larger enterprises underwent corporatisation and turned into joint-stock companies. In some cases, the Sakha government retained a portion of shares on behalf of the republic (especially in strategic industries such as diamonds), but even there, significant chunks went to workers. A prime example was the region’s crown jewel, the Yakutalmaz diamond combine, which was reorganised in 1992 into a new company called Alrosa (short for “Almazy Rossii Sakha”, meaning government initially secured a sizable stake for itself and the local districts but, importantly, 23% of shares were allocated to the company’s workers and another 5% to a federation of miners’ veterans.

The Russian federal government held a stake roughly equal to Sakha’s. In essence, even the massive diamond mines followed the spirit of Louw’s ESOP recommendation: Miners and engineers suddenly were shareholders in the mines where they toiled. By the late 1990s, Sakha’s regional authorities and Alrosa employees together controlled a majority of the company, a fact that gave the republic considerable leverage, and which Moscow eyed jealously as the decade wore on. It’s telling that in 2001, as Vladimir Putin reasserted central authority, the Kremlin ordered audits of Alrosa and manoeuvred to increase the federal share; Mikhail Nikolayev even transferred the republic’s shares into a private trust at one point to thwart a Moscow takeover.

Eventually, the federal government did manage to boost its stake to just over 50%, diluting Sakha’s control. But the legacy of the 1990s privatisation remained: A large chunk of Alrosa was owned by employees and local governments, not just Moscow’s treasury. Beyond diamonds, Sakha’s privatisation saw state farms turned into cooperatives, and service industries like trade and catering moved into private hands. Some enterprises undoubtedly ended up effectively in the hands of their former Soviet-era directors, who now wore new hats as capitalist entrepreneurs.

Whether this was a success or not depends on your point of view. From Louw’s perspective, the fact that Sakha managed to privatise without violent upheaval or paralysis was a victory in itself. The ofcials who might have derailed the process were instead learning how to run their businesses for profit. A few certainly enriched themselves, but they did so by improving output rather than by pillaging. One hopes.

As for De Beers, it ultimately did not become a mining operator in Sakha. Part of the reason was technical and economic: As Louw learned, mining diamonds beneath a kilometre of permafrost is extraordinarily costly and complex. The rich grades of diamonds in Yakutia were locked in pipes deep underground; open-pit mines like the famous Mirny mine (a gargantuan hole in the ground more than 500 metres deep) had been exhausted by 2001.

New mining had to go deeper, under frozen earth, something never done profitably at scale. Sakha’s own company, Alrosa, eventually mastered some of these challenges by the 2000s with underground mines, but it was a slow road. De Beers, perhaps wary of the economics of mining in Sakha, stayed mostly on the sidelines. For a period in the 1990s, De Beers did assist in marketing Yakutian diamonds; under a trade agreement with Alrosa, De Beers bought a significant portion of Russian production to sell via its global syndicate, helping stabilise prices.

But even that cooperation ended around 2008 due to European Union competition concerns. In essence, the grand vision of a joint Oppenheimer-Sakha diamond venture never fully materialised. Instead, Alrosa rose as a giant in its own right. Today, it is the world’s largest diamond mining company by volume. In 2024, Russia (mainly via Alrosa’s mines in Sakha) accounted for about 32% of the world’s rough diamond output by carats, surpassing even Botswana. The Sakha diamonds that had once been covertly funnelled through De Beers’ channels are now sold directly on world markets, especially since Western sanctions in recent years curtailed some trade. It’s a development that perhaps neither Louw nor the Oppenheimers fully foresaw at that 1993 dinner. The permafrost was indeed thawed.

From the department of peak AI questionmark ..

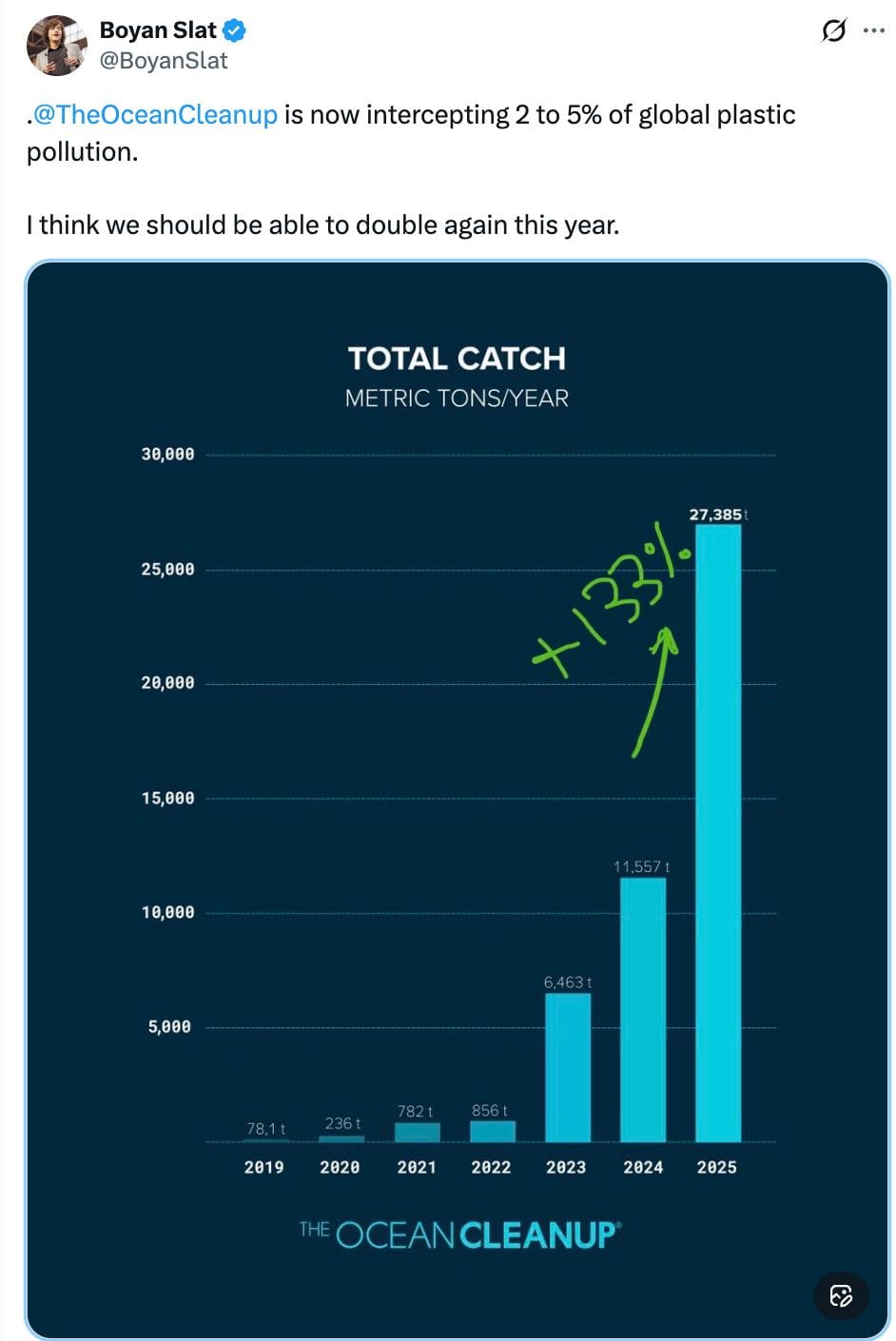

From the department of maybe this is actually possible ..

Thanks for reading - please do share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

By all means, comment on the post - I'm interested in all feedback, good, bad, indifferent.

Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation