There are few things more fun than seeing economists having a fat go at each other and getting proved wrong by history. Perhaps that’s an overstatement; the spectacle of economists arguing is perhaps not a Monster Jam big-wheeled-truck-race excitement. But you know, in the world of verbal battles between brilliant intellectuals, economists getting their comeuppance has to be up there. In a way.

As it happens, the wrongedness of economists has a long and rich history. When it happens, which is, let's be honest, pretty often, the economists tend to metaphorically shuffle their feet and mumble something about the “dismal science” incorrectly, as it happens.

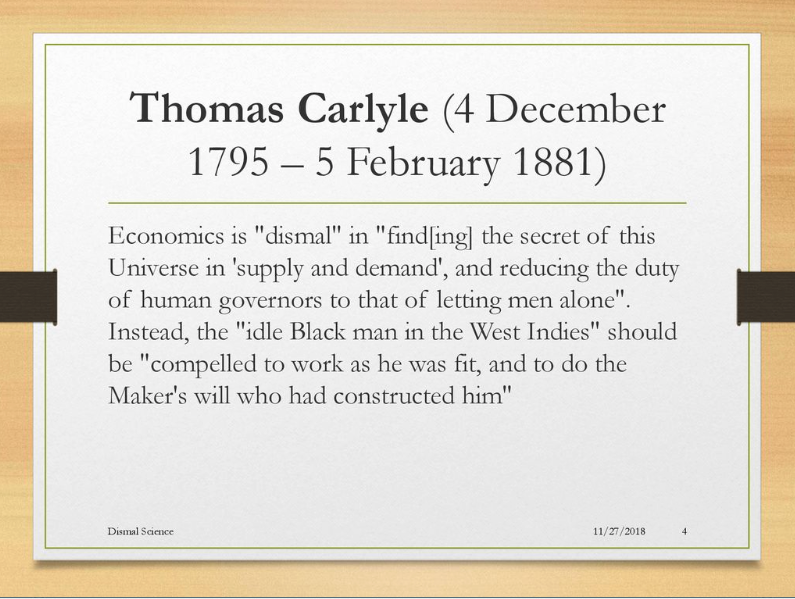

The phrase “dismal science” was coined not because economics deals with constraints, trade-offs, scarcity, inequality, crises and recessions. Neither was it called the dismal science because it deals overwhelmingly with tangible material objects using large quantities of equations, as opposed to the hallowed humanities, which deal with lofty culture and morality.

When Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle first used the phrase in his 1849 essay (and I am not making this up), “Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question”, he was seeking to repudiate the ideas of economists like John Stuart Mill and Adam Smith.

Mill and Smith were - get this - arguing against slavery, based on the idea that free people working voluntarily in a free market would be more productive and morally superior than coerced labour. So much for economists shunning culture and morality in favour of mathematical equations.

Carlyle was arguing in favour of a rigid social hierarchy and ridiculed the idea that anything other than slavery would result in greater economic value. The notion was “dismally” idealistic and impractical, in his view. And thus began a long history of economists being right and essayists being wrong. Well, not quite. Alas.

As it happens, we stand at a crucial time on this very question and finding a logical path through this conceptual maze has really never been more important, particularly for that perennial patient, South Africa, standing again at a crossroads, as it has so often in the past.

The crisp question is this (actually, it's not all that crisp): should SA learn something from the extraordinary positive changes Argentina’s President Javier Milei has brought about in a little more than a year? And if so, what?

There is a related and perhaps even more complicated question: Milei and US President Donald Trump are considered loosely to fall in the same camp. The famous chainsaw of Milei’s political rallies has now appeared frequently in US politics, particularly in the hands of Trump’s sidekick and head of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), Elon Musk. (And is there any name more creepily reminiscent of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four than that?)

But if it is true that they are peas in the same pod, why do Milei’s policies of aggressive austerity and free-market reforms seem to have worked, while Trump’s policies in broadly the same broad vein seem to have backfired? Just one measure tells us - not the best, I know - but Argentina’s Merval stock market index is up 70% since Milei took over, while the S&P is down about 10% since Trump took over.

But I digress. Let's get back to that hand-rubbingly fun question of economists being wrong. Just as Milei was about to take over unexpectedly as president a little over a year ago, more than 100 leading economists signed a letter warning that his election would probably inflict further economic “devastation”. (Side issue: never sign speculative letters designed to signal your moral superiority.)

The letter said, “ … while apparently simple solutions may be appealing, they are likely to cause more devastation in the real world in the short run, while severely reducing policy space in the long run.” The signatories included all of the well-known lefty economists of our era: France’s Thomas Piketty, India’s Jayati Ghosh, the Serbian-American Branko Milanović and Colombia’s former finance minister José Antonio Ocampo.

They complained that Milei’s dollarisation and fiscal austerity proposals “overlook the complexities of modern economies, ignore lessons from historical crises, and open the door for accentuating already severe inequalities.” The writers used all the favourite tropes of leftwing economics, describing their ideological opponents as “far right-wing”, “dangerous” and “damaging”. They worried not only about Argentina but about the whole continent!

Well, it's early days - they might still be right. But the portents of the apocalypse do not appear to have materialised. Based on Milei’s personality - erratic, prone to furies, and provocative - it was easy to jump to the conclusion that his administration would be erratic, prone to furies, and provocative. Yet, amazingly, it has just all worked.

Milei's government drastically cut public spending by 30% in real terms during his first year, including eliminating subsidies on energy and transportation, reducing the number of ministries and public sector jobs, and closing the tax agency AFIP, replacing it with a smaller agency.

The result is that inflation is down from an annual rate of close to 140% a year to now 3% in a month. The recession is gone, and there has been a primary budget surplus for the first time in a decade. Most importantly, Milei was upfront in his election campaign that there would be pain at first, which there was since the poverty rate went up. According to the latest INDEC (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos) measure of income poverty, the current poverty rate is now lower than it was four years ago. All this happened in just one year - it’s amazing.

What particularly worried the critical economists was Milei’s attack on the Argentine central bank, which he threatened to abolish and dollarise the economy. But he has followed through on neither promise. The current focus remains on stabilising the economy through fiscal discipline and monetary reforms, which have curbed excessive money printing.

He prohibited the Central Bank from printing new pesos to finance government spending; changed the exchange rate from a crawling peg to a managed float (a much freer system); and lifted capital controls.

And then there are tariffs: generally, both import taxes on consumer goods and export taxes on agricultural goods have been cut, but interestingly not scrapped entirely. He has surrounded himself with academics and experts with widespread support and respect. To me, it's amazing how careful he is, despite being characterised as manic. And he's been humane as it happens, introducing and supporting measures to limit economic hardship.

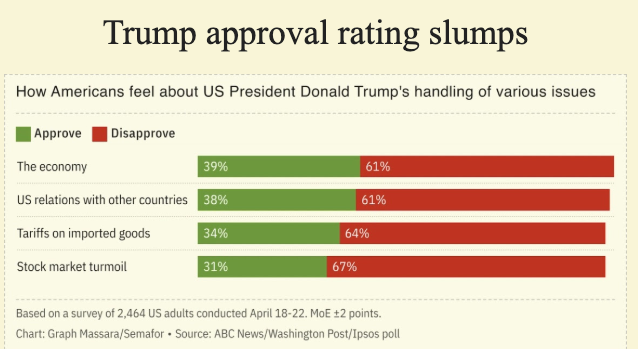

Just contrast all of this to the first 100 days of Donald Trump, which actually have been manic. Trump’s overwhelming focus has been on trade tariffs, which have gone up, gone down, been implemented, been scrapped - it's almost impossible to know what the actual policy is on any given day.

Trump’s appointments to key positions are just loony, and include some of the most genuinely weird people in American politics. These include Pete Hegseth as Secretary of Defence, a former news anchor, and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as Secretary of Health, a well-known vaccine sceptic. I mean, WTF?

But that’s just the start: Kristi Noem as Secretary of Homeland Security, Tulsi Gabbard as Director of National Intelligence, Peter Navarro as Senior Counsellor for Trade and Manufacturing (among many others), who all seem patently ill-equipped for their jobs. Trump's Secretary of Education, Linda McMahon, referred to AI as “A1", like the steak sauce! What binds them is that they are unconventional, but more importantly, fiercely loyal to Trump, whom they publicly laud in televised cabinet meetings in ways reminiscent of cartoonish satires of the vain leaders of authoritarian states.

All this we know, but look deeper, and the common threads between Milei and Trump become clearer: the anti-establishment rhetoric, the big-man persona, the excessive use of executive power. And yet, on examination, the differences become clearer too.

The most obvious is that the starting points are different: Argentina was facing a catastrophic economic crisis, while the US economy was puttering along just fine, thank you very much, despite the shocking price of eggs.

In this context, inflation control and fiscal discipline are measurable, tangible wins in a country traumatised by economic chaos. Milei is the solution, not the problem. Trump’s tariff vacillation makes him seem like the cause of economic chaos: he is the problem, not the solution. Austerity is seen in Argentina as necessary to defeat the inflation dragon, so not so much Milei’s choice but a necessary response to an economic crisis. The tariff war is seen, rightly, as primarily Trump's choice. It's the difference between economic necessity vs. political choice.

Milei has weak congressional support, which ironically helps because he is viewed as an outsider, while his academic background as an economist lends credibility to his reforms. Trump’s strong congressional support ironically hurts because he has nowhere to defray his failures. Milei has great global and investor support; Trump is quietly despised by global leaders and is now openly criticised by senior US businesspeople.

There is much more here, but all of this illustrates an overwhelming point: context matters. And details matter.

So … to return to the original question, is there something Milei is doing that SA could learn from? Plenty - but also not.

The obvious difference is that on the good side, SA is far from facing an inflation crisis, and on the bad side, it is more broadly a poorer country.

Yet, what Milei’s approach does suggest is that the argument that deficit reduction increases poverty over the longer term is wrong, or at least not necessarily right. On the contrary, it can increase wealth. Socialist governments don’t like to cut public welfare because, very understandably, they worry it will increase societal stress and actual hunger.

However, deficit reduction often increases the government's ability to spend by stabilising debt and reducing borrowing costs. Around 27% of the SA population now relies on government grants, and there is a risk of social unrest if they are cut. But cuts could easily be made elsewhere, which would provide the fiscal room to increase the grants.

It comes down to the question of whether government austerity is seen as an economic necessity or as a political choice: SA doesn’t have the luxury of a full-blown crisis, although in time it might. At the moment, South Africa’s fragile political climate may not tolerate more pressure.

Price controls are also rare in SA, in contrast to Argentina, so that too is a big difference. But SA could learn from the loosening of exchange controls and deregulation. South Africa’s global competitiveness is poor and slipping, attracting FDI of only around $9 billion annually, low for its size.

What Argentina illustrates is how fast the effect of these changes can be felt. But unlike Milei’s confrontational style, South Africa needs bipartisan support (ANC, DA, IFP) to pass reforms, precisely because of the economic necessity vs. political choice dynamic.

There is a lot more that could be said in this vein, but I suspect the point is made: Context matters. Details matter. 💥

From the department of when you are hot, you are hot ...

From the department of the rich getting richer ...

From the department of vorsprung durch if at first you don't succeed ...

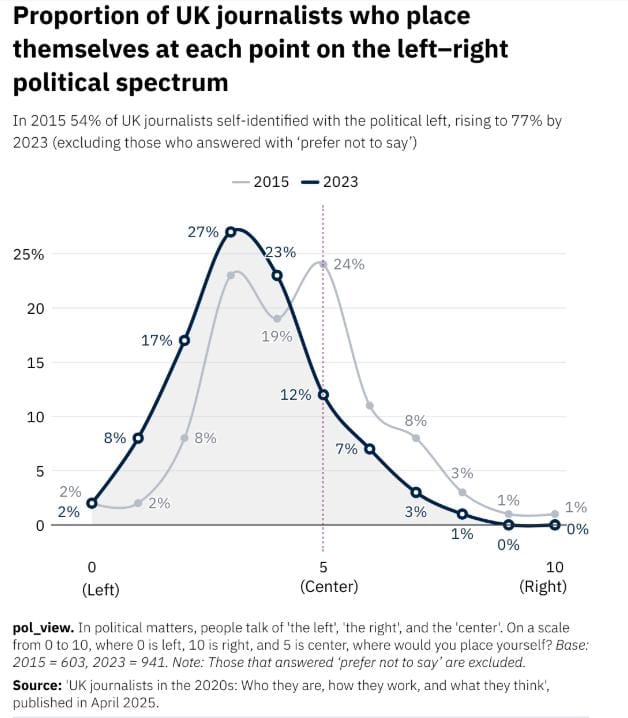

From the department of the gradual disappearance of the centre ...

Thanks for reading - please do share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value it and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation