I don’t do it very often, but every now and then, I decide to go to war on Twitter (X) by doing something outrageous, like trying to inject a little common sense into a conversation. I know. I know. Stupid. No attempt at being sensible ever goes unpunished on social media. Intelligent, fact-based centrism is now regarded as the prattle of fogies who believe in facts and stuff.

But you know, sometimes you just can’t help it. I should leave Twitter, but it took me years to gain a small following on X; it seems such a waste to just walk away. I have joined the other platforms, but for better or for worse, X is the closest thing we have to a public square, so now and then I glance at it, and promptly get annoyed. Social platforms are rooted in the need to grab your attention, so almost by definition, engagement is enragement. But not all the time; there is lots of humour, advice, ideas, moments of serendipity, and beauty.

There is another thing. As much as I hate thoughtless anger, it does sometimes serve a purpose. People are less constrained and more revealing when they get angry, which is why public relations people always advise their clients never, under any circumstances, to get angry with anyone. The result is often a false public discourse. So, throwing a bit of invective into a situation can actually be interesting.

And this one definitely was, in both good and bad ways. Let me take you through it (sorry, this is long, but revelatory).

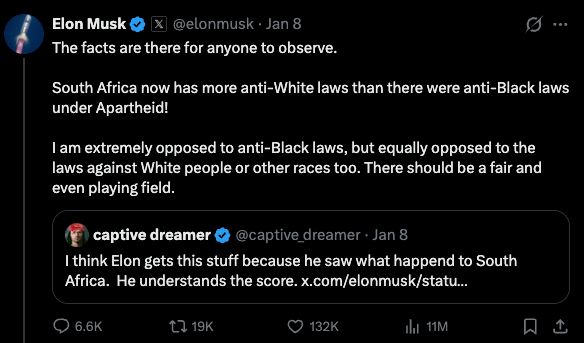

What irked me was a tweet by the owner of X, Elon Musk. This was the tweet:

This was my response:

Many people have made similar arguments about Musk’s illogicality (and that of the SA organisations that put out this rubbish), but I wanted to make two additional points.

The first is about the geographical foundation of Apartheid, which people seem to have somehow forgotten if the “quantity of laws” argument they pose all the time is anything to go by. Perhaps people generally don’t know this unless they actually lived during apartheid.

In addition to being a racist system, Apartheid was fundamentally a geographic system, rooted in the notion of physical separation. Because people who lived in Soweto, for example, were theoretically “guests” in what was demarcated as a “white area”, Soweto spaza shops were not allowed, for a time, effectively prevented from carrying non-perishable items because "general dealer" licences were not granted to spaza shop owners. That would have implied Soweto residents were “permanent” residents in a "white" area, God forbid. Generally, spaza shops were confined to offering milk, mielie meal, sugar, and a few other basic low-margin goods, because most were effectively operating illegally.

Gradually, the rules were relaxed over time under protest, but still, the point is that there was no racial reference in these regulations; they applied geographically to people who happened to be black. And there were thousands of them. Thousands. The administrator of Soweto had more power over the lives of Soweto residents than dictators typically have over their subjects. They were technically “regulations”, but in effect, they were racially oppressive. To simply count discriminatory laws seems a deliberate misconstrual of the situation.

And on that topic, I really struggle to understand where Musk is going with this stuff. He has moved from being a politically ambiguous centrist to repeatedly amplifying racially charged white identity politics that overlap uncomfortably with white supremacist talking points. He is now way to the right of the Republican Party. His tweet claims he is against all racially specific legislation, positioning himself as race agnostic. But just this month, he reposted a message that argued that if white men became a minority in the US, they would face “slaughter,” and said “white solidarity is the only way to survive,” adding a “💯” emoji.

This is pure “swart gevaar” politics from the old South Africa in its most venal form. It's just sickening - and disappointing. This post was widely criticised as aligning with white identity politics that overlap with white supremacist talking points. His politics now seem to be a mirror of his father’s - straight-up, unreconstructed old South African, paternalistic, ideological racist bunk. SAD!

But what I secretly hoped would be controversial, and indeed became so beyond my reckoning, was the final bit of my tweet, suggesting that we should still allow Starlink to operate in SA. Wouldn’t that be a kind of endorsement of his racism? I don’t think so, and I will argue my case here, but I would concede that Musk’s repulsive politics do make it an infinitely tougher sell. However, I think the argument still works - you tell me.

But first, just to get the alternate argument down, here is my old mate and colleague Songezi Zibi, now Rise Mzanzi MP and leader, arguing the opposite point of view.

Zibi's position was supported by a large number of people; he got about 7500 likes, and lots of verbal support - far more than the 400 or so who supported my position (notably, tens of thousands supported Musk’s). But it is worth noting, the argument didn’t entirely go Songezo’s way … and obviously neither did mine. But here is the thing: All of these likes, all of this positioning and arguing, all of these comments from the benign to the profane, ALL TOOK PLACE ON X - A PLATFORM OWNED BY MUSK.

So why, if these players who claim to despise Musk and his politics so much, are they still on X? If you are claiming that Starlink is a CIA plot and a threat to the sovereignty of South Africa, why on earth then would you implicitly support X by participating on it?

Actually, I think I know why. Because, for all his awfulness, there is a difference between the way X is run, its utility, and Musk’s personal role in the whole thing. Even though he owns it, X is still useful, in its own odd way.

Soo ... doesn’t exactly the same argument apply to Starlink? The very reason this debate is taking place is that Starlink is abiding by South African law, applying for a licence to operate, and arguing, with support from the ministry concerned, for an equity equivalent status, like so many other US and Chinese and European tech companies.

There is a good example of the difference between Musk’s views and how Starlink operates out there. During the 2024 conflict around Brazil’s suspension of X, the Brazilian regulator and the judiciary became entangled in enforcement, and Brazil’s regulator threatened to sanction Starlink as tensions spiked. Starlink publicly condemned state actions but signalled it would comply with a blocking order following the legal directive — illustrating the operating-legally-but-publicly-at-odds-with-the-state dynamic. Musk and Starlink (which has lots of shareholders other than Musk) do undertake to operate under local laws, and have a history of doing so.

For example, it would be easy for Starlink to allow South Africans to register their Starlink terminals in Botswana or Eswatini and use them in SA, but it is Starlink that prevented South Africans from doing so mechanically. When the SA regulator, Icasa, told them to stop, they did.

But let me argue against myself for a bit. I think it is too easy, and intellectually lazy, to dismiss all opposition as anti-technology, anti-market, or reflexively anti-Western. Some of the concerns raised deserve to be taken seriously.

First, there is the sovereignty and security argument. Satellite infrastructure is not neutral plumbing. In Ukraine, Starlink has been tactically decisive. In Iran, satellite connectivity has been framed by both activists and governments as a regime-threatening capability. States are not irrational to worry about who controls the communications infrastructure that bypasses terrestrial regulation.

Second, Starlink is not a small startup seeking benign integration. It is controlled by an individual who has demonstrated an unusual willingness to use platforms he owns as instruments of political influence. Musk’s stewardship of X has blurred the line between free speech absolutism and editorial intervention, which, understandably, unsettles regulators in a country still traumatised by information warfare.

Third, South Africa has a long and unhappy history of foreign companies extracting value while leaving little behind. Scepticism about yet another foreign tech firm promising salvation is not, in itself, delusional.

But my argument is that taken together, these concerns justify regulation. They justify scrutiny. They even justify delay. What they do not justify is abandoning the law.

Consider some of the arguments made by the anti-Starlink crowd. I would say they fall into two groups: the hard-line BEE defenders, who claim any criticism of race-based policy is an attempt to restore white privilege or deny apartheid’s legacy. And then there is the nationalist / conspiratorial fringe, which argues that foreign companies, the US, or the CIA, are attacking SA sovereignty through tech. By all means, have a look at the comments.

IMHO, this is deliberately overstated for the enragement effect. The facts here are that about 2.7 million households in South Africa have active fibre connections, roughly 15 % of all households. But, about 78.9 % of South Africans use the internet (via any technology, mobile or fixed) as of early 2025. That means there are a huge number of people using their cellphones - and only their cellphones - to get onto the internet.

But the cost differences are ridiculous. You don’t pay “per gigabyte” for fibre, but if you did, it would cost the equivalent of around R1 per gigabyte. The average cost per gigabyte on the cellphone network is R35. It's extreme.

In the thousands and thousands of responses to this debate, these numbers are never cited. The fibre companies, a market in which the cell companies also play, just can’t reach South Africa’s rural population, which condemns rural South Africa to extremely expensive internet. There are ways of getting around this with line-of-sight systems, but they provide nothing remotely close to the speed-of-fibre connections. And that tells you everything you need to know about why the cell companies are against allowing Starlink to operate in SA - they are making a fortune out of data sales, and they don’t want the competition.

From a developmental, cost and rural-provision point of view, there is no realistic current alternative to Starlink, which is why there is so much pent-up demand in rural areas for Starlink. And all the anti-Starlink proponents, who are massively free with their commentary as we can see from the comments to Zibi’s position and mine, seldom address this point, and never give it the attention it deserves. Why? I think its partly that they don't live in reral South Africa. It doesn’t make any difference to them personally, so they resort to political posturing.

What about the legal issues? This we have been through a zillion times: just for the record, the Electronic Communications Act, 36 of 2005 (ECA) is the primary statute governing all electronic communications in South Africa. Under the ECA, Starlink must obtain an ECNS licence (Electronic Communications Network Service) because Starlink operates a communications network (even if the satellites are in space. ICASA regulations have been historically stricter than the general ICT sector code, requiring greater than 30% ownership by "historically disadvantaged persons" for both ECNS/ECS licensees. This is not written directly into the ECA, but imposed via ICASA licensing regulations and past licence invitation conditions.

The ICT Sector Code explicitly allows Equity Equivalent Investment Programmes (EEIPs) for multinational firms, and ICASA’s historic licensing rules did not fully align with the ICT code. This mismatch is why the Minister, Solly Malatsi, issued a policy direction, instructing ICASA to align licensing rules. Icasa, it's worth noting, did grant fresh spectrum licences in 2022, but only after a decade of argument. And that is one of the reasons why SA is so behind technologically, and at least one of the reasons why South Africans pay so much for internet data: Competition is constrained.

Starlink’s central proposal is not to sell 30 % ownership to local shareholders, but to meet South Africa’s Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) goals through EEIPs instead. Examples include skills development, enterprise support, supplier development, infrastructure investment, and digital inclusion initiatives. This approach is already recognised by the broader ICT Sector Code and has been used by other tech companies operating in South Africa.

Starlink has publicly signalled tangible commitments it would make if allowed to operate under EEIP-style compliance, including: R500 million worth of investment into activities that align with empowerment goals, and crucially, free high-speed internet for 5,000 rural schools, potentially benefiting about 2.4 million students per year, through partnerships in local communities.

To me, that is a pretty good deal. I’m prepared to hold my nose at Musk’s horrible politics if it benefits 2.4 million students. But to the opponents of Starlink, the issue is not only about BEE; they have moved their ground. It's about sovereignty and constitutionality; Musk is just not bending the knee to our "constitutional requirements".

But this is also contested. I do wish the people who claim that BEE is a constitutional requirement (basically all South African politicians) would actually read the constitution. The constitution sets equality as a goal, and it permits limited racial intervention to achieve that end, given South Africa’s history. Section 9(2) says: "To promote the achievement of equality, legislative and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination may be taken". But then the very next clause 9(3) says: “The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.

The courts' approach to this fine distinction is that the Constitution does not mandate racial quotas; does not require ownership transfer to specific racial groups, does not require permanent race-based classification and does not endorse racial “outcomes” irrespective of cost or competence. The Constitution permits race-conscious remedial measures under section 9(2), but it simultaneously entrenches non-racialism as a founding value. BEE is therefore constitutionally allowed, not constitutionally required. And only so long as it remains genuinely remedial, proportionate, and transitional. The constitutional destination is not permanent racial management, but a society in which race no longer determines access to opportunity.

That actually provides quite a lot of ammunition to Musk, who claims he is being discriminated against because he is white. In a sense, Musk is not actually contesting SA’s constitution; he’s supporting it! (Or at least the proportion of it that supports his arguments). As it happens, I think that much of the world would generally agree with him that requiring investors to give away equity on the basis of their race is a bit of a problem, even if South Africans understand it differently. So he is able to make great hay out of not being granted a licence in SA, and it would be very nice if this went away.

It's true that some countries also require local ownership: the US itself caps foreign ownership of broadcasting and media companies at 25% (although there is no cap on the foreign ownership of telecoms or internet companies). A lot of African countries restrict foreign ownership of internet providers - mainly so they can close them down if something intolerable, like political opposition, emerges, as we have seen all too often.

So, to make a long story short, Starlink has weirdly become a Rorschach test for South Africa’s unresolved relationship with power, race, law, and technology.

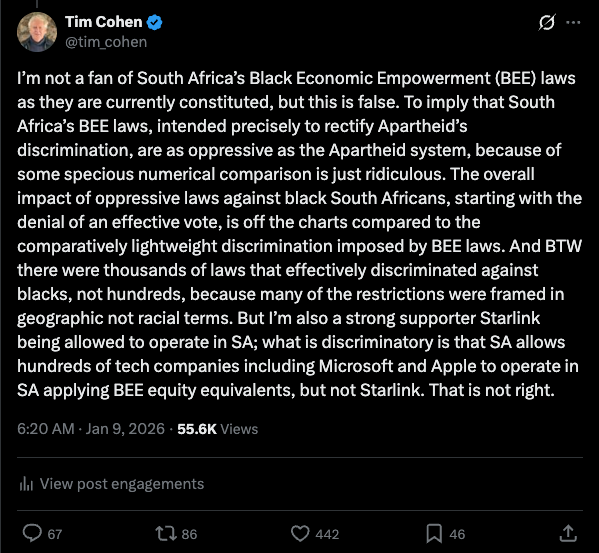

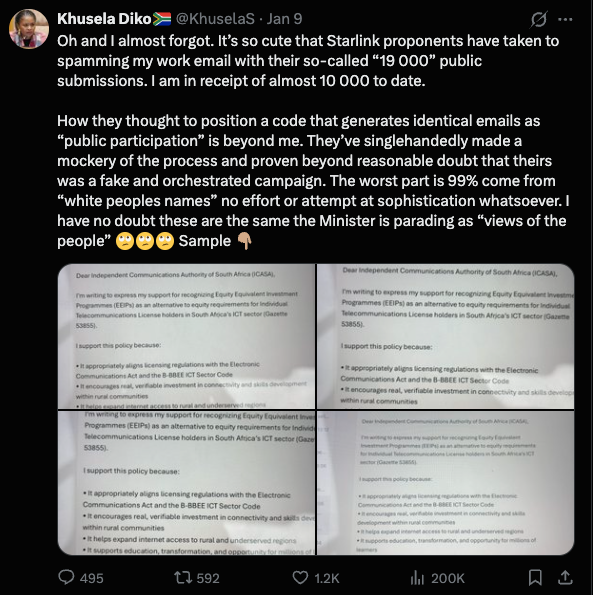

But before I leave this all, there is one other thing - and it's very important. In response to this argument, Khusela Diko, former presidential spokesperson before she was dropped when her husband apparently engaged in some dodgy BEE stuff during Covid, tweeted this in support of the anti-Starlink faction:

Dico is an ANC NEC & NWC Member, and is also Chairperson of Comms & Digital Technologies subcommittee, so in an absolutely crucial position in this debate. Now I sympathise with her getting spamming on her work email (although it takes two seconds to move all that stuff into its own directory), but this is a curious response for a lot of reasons.

She questions how Starlink managed to create a “code” that generates identical emails, and claims that this proves this is a fake and orchestrated campaign. But the explanation is obvious: Starlink asked its applicants to support its campaign by approving an email and sending it to the relevant decision-makers of which Dico is one. Marketing campaigns do this all the time; it's definitely orchestrated, but definitely not illegal. I get gobs of marketing emails. But it does not suggest their support is “fake”; it demonstrates they are actually genuine, and surely Dico, as a public representative, should respect their views and not pretend the whole thing is "fake".

But the amusing part is that Dico points out that the names on the emails were mostly “white people’s names” and says this demonstrates there was “no attempt at sophistication" at all. I don’t know what Dico is suggesting here, but it sounds like she is suggesting that a “sophisticated” campaign would have faked the names. But in fact, that doesn’t suggest the support for Starlink is “fake”; it suggests the opposite, that it's genuine.

Another thing. By publishing screenshots of unredacted emails, Diko may have exposed herself to questions under POPIA, which places strict duties on public officials regarding the disclosure of personal information. Whether this crosses the legal threshold would depend on context, consent, and purpose—but it was, at minimum, a reckless thing to do.

Section 14 of the constitution protects the right to privacy, and this is manifest in Section 11 and13 of the Protection of Personal Information Act (Popia), which prohibits a state official from disclosing personal information without a lawful basis in a way that is excessive or harmful. The fact that she didn’t obscure the email addresses before tweeting them, which would have taken seconds, suggests she didn’t think they were genuine. And that’s very instructive, because it suggests she doesn’t believe the supporters of Starlink are themselves genuine.

So here is a question: how is Dico’s repugnance at the fact that the Starlink supporters who supported an email pointing out the legality and utility of the Starlink application, are “white people’s names” (spit!) different from Musk’s repugnant racial views?

I just leave you with that. 💥

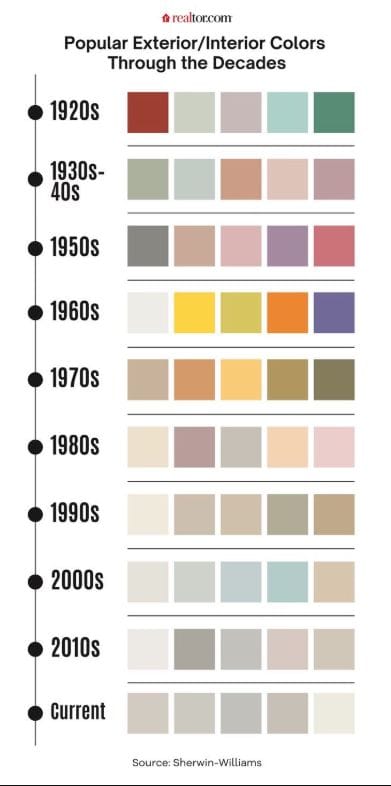

From the department of it's all got a bit dull ...

From the department of glimmers of hope in the dystopia ...

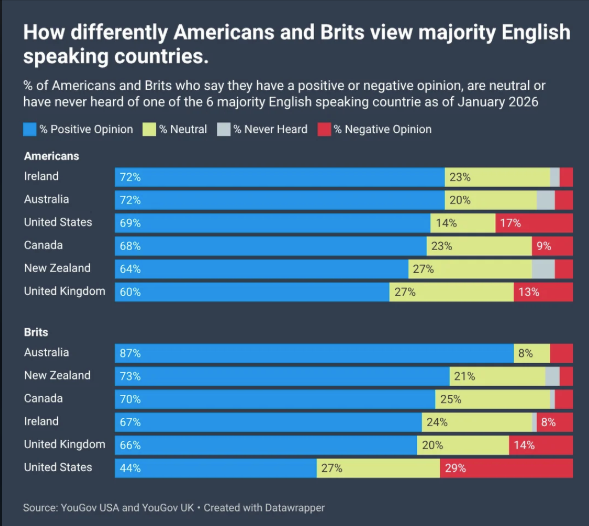

From the department of Brits not being crazy about people from the UK. But then Americans are not crazy about people from the US either ...

Thanks for reading - please share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation