This is such a great question — and it feels more relevant today than ever.

I started thinking about it after reading a New York Times column by Bret Stephens. His inquiry was slightly different: “Do dumb ideas ever die?”

I think the answer is yes — sometimes. But that doesn’t explain why some bad ideas persist in public consciousness far longer than they should. Stephens was writing just after Zohran Mamdani was elected mayor of New York. A whole bunch of publications, including in South Africa, heralded his election as a fabulous rejoinder to the craziness and cruelty of the Donald Trump era. And in some ways he does at least present a fresh face of the moribund Democrats.

But the sad truth is that both Mamdani and Trump are, in their own ways, first-degree proponents of the question itself: Why do dumb ideas never die?

Mamdani’s Bad Ideas

Let’s start with Mamdani. As a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, his election program included four very dubious ideas:

- A rent freeze on rent-stabilised apartments

- Free buses

- A $30 minimum wage

- A city-owned grocery store in each borough

So why are these bad ideas?

The generic answer is that consistent, historical examples demonstrate that they all unleash a furnace of unintended consequences. Rent freezes share the same fundamental flaw as rent control itself — they distort incentives without addressing underlying supply constraints. Landlords lose the incentive to maintain or invest. The gap between controlled and market rents widens. Over time, the housing stock deteriorates, new construction slows, and shortages worsen.

This is not theoretical — it’s demonstrable. Where, you ask? Well, New York, for one. But also everywhere else it’s been tried.

What about free buses? That can’t be bad, can it? The problem is that it addresses affordability by suppressing prices rather than increasing supply. It’s the economic equivalent of cooling a fever by breaking the thermometer.

And the $30 minimum wage? Haven’t studies shown that minimum wage increases don’t necessarily hike employment?

Well, partly true. Economists find that moderate increases (say 10–20%) can raise earnings with little job loss. But huge jumps — doubling or more — risk pricing out marginal firms and low-skill workers. It confuses moral ambition with market capacity. A wage floor that exceeds productivity becomes a wall against entry.

There’s an important caveat here, as South Africa demonstrates. In 2019, there was a big debate about raising the minimum wage to R20/hour. It has since risen about 38% to R27.58/hour — well above inflation. Economists differed on whether this would raise unemployment, with the most conservative studies predicting a 1–3% increase. In fact, that estimate proved broadly correct: unemployment has risen by 2.5 percentage points over that period. Yet some data suggest the proportion of the working poor has decreased.

South Africa’s minimum wage was introduced cautiously; even back then, a large proportion of the labour force earned above R20/hour.

So this rates as a “bad idea” not so much because of the principle, which is arguable, but because the extent of the increase Mamdani proposes would effectively double the minimum wage. At that level, you’re well into unintended-consequence territory: automation, off-the-books employment, or business relocation.

The “ANC-esque” Grocery Store

But the most “ANC-esque” idea is the notion of a city-owned grocery store. The implicit claim is that private supermarkets are monopolistic and therefore guilty of price gouging. But retail requires constant efficiency, supply-chain agility, and pricing precision, all of which bureaucracies famously lack. Political interference in pricing and sourcing is inevitable, leading to inefficiency, waste, and dependence on subsidy. Private grocers are crowded out; innovation is discouraged.

How many times have we heard the ANC argue that the big problem is “monopolistic businesses,” and that “our people” should therefore be supported by the state? Monopolies do exist in some industries, but retail is seldom one of them. The idea that monopolies dominate a fiercely competitive market like New York is just nuts.

Bad Ideas on the Republican Side

On the Republican side, bad ideas also abound. Two standouts: tariffs and vaccine scepticism. You can tell they’re bad because criticism elicits not debate but apoplexy.

Take Trump’s tantrum against Canada after Ontario aired a television ad quoting Ronald Reagan’s 1987 warning about protectionism. Trump immediately declared an end to trade talks with Canada, claiming Reagan “LOVED tariffs.”

As The Wall Street Journal pointed out, Trump was wrong twice: Reagan did not “love” tariffs, and his 1987 speech was an exception — a narrowly targeted protection for the semiconductor industry against Japan.

Reagan’s semiconductor tariffs did briefly boost U.S. chip production — from about 30% to 50% of global supply. But guess what it is today? About 10%. And the winners weren’t Japanese firms like Hitachi or Toshiba, they were Taiwanese upstarts like TSMC. Reagan should have trusted his free-trade instincts.

Ironically, Mamdani’s victory underlines Trump’s miscalculation. Recent Democratic wins in U.S. elections were underpinned by stabilising consumer affordability — the very issue that got Trump elected in the first place. His tariff tantrums haven’t hurt consumers much, mainly because he keeps backtracking on his threats, but they certainly haven’t helped.

The Vaccine Delusion

Perhaps the most dangerous “bad idea” in circulation today — though not uniquely Trump’s — is vaccine denialism, championed by his Health Secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Antipathy toward vaccines is not just mistaken; it’s dangerous, contagious, and repeatedly lethal. The World Health Organization estimates vaccines prevent 4–5 million deaths every year. Smallpox has been eradicated, polio is 99% eradicated, and measles deaths have fallen 80% since 2000.

The science is unambiguous. Yet the idea persists because it offers narrative comfort — transforming complex fears (autism, corporate power, government control) into a simple scapegoat story.

Why Bad Ideas Persist

Bad ideas endure because of human nature. They feel good. They offer simple answers to complex problems or confirm what people already want to believe. A comforting falsehood is more appealing than an uncomfortable truth.

They provide moral clarity or identity — telling people who the heroes and villains are. The emotional reward of belonging (“we few, we proud, the rational ones”) outweighs any empirical rebuttal. Once belief becomes tribal, evidence becomes treason.

There’s inertia too: organisations and industries build up around bad ideas. Careers, investments, and power structures depend on them. The sunk-cost fallacy kicks in: “We’ve already invested so much — we can’t stop now.” Admitting error feels like failure.

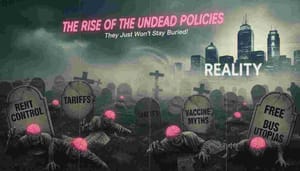

And often, bad ideas have a kernel of truth — a sliver of something real — that makes them sticky. And isn't this the trouble with bad ideas? They’re like zombies: they never really die; they just change clothes and come back looking “policy-relevant.” You can shoot them with data, stab them with logic, or bury them under peer review, but they still stagger out of the graveyard of good intentions, moaning: “Let’s form a task team.” 💥

For paying customers, I have a few thoughts about overcoming bad ideas. Please subscribe if you’d like to read further — this article is already long, and I won’t keep you. But for those who like solutions, subscribing is cheaper than chips, and you can read on.