In a televised address on Sunday, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced he had established a judicial commission of enquiry to investigate the explosive allegations made by KwaZulu-Natal police commissioner Lieutenant General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi that Police Minister Senzo Mchunu was colluding with criminal networks and had obstructed major investigations into politically motivated killings. Mchunu, who denies the charges, was put on leave.

There is a lot to say about all this, but allow me to break it down into the main aspects, good and bad.

Let's start with the good.

- There has been understandable sighing about the fact that we have yet another commission of enquiry. The police task force into political killings that Mchunu disbanded was itself the product of a commission, the Moerane Commission, which was set up in 2016. It was a pivotal commission exposing why KZN politicians were being targeted—mainly over lucrative tenders and internal power struggles—and laid out robust reforms. But in the way of these things, there was no sustained follow‑through; the same dynamics that fueled the violence continue to fester.

But the problem is that it's constitutionally and legally impossible, not to mention unjust, to condemn without cause, so the legal avenues left to the president are narrow. Establishing a judicial commission of enquiry, led by Acting Deputy Chief Justice Mbuyiseli Madlanga, does ensure an independent probe into the allegations.

- There is a time limit. With all the commission of enquiry fatigue in SA, Ramaphosa is aware that the public wants action this time. Madlanga is required to issue an interim report in three months, a second interim report in six months, and then a final report later. That, of course, still allows the perpetrators to cover their tracks, but at least there is some sort of political recognition that we are all getting very tired of this, and it betrays the fact that he is embarrassed about it all, as well he should be.

- Mchunu has rightly been put on ice. Political parties responding to this make the obvious point that Mchunu is going on a long holiday, otherwise known as suspended-with-pay, similar to so many other perpetrators of dodge. But once again, Ramaphosa is constrained by law, so his remit is narrow.

There are other good things, but let's turn to the bad.

- The remit of this commission is ridiculously wide. It is tasked with probing allegations that senior current or former officials facilitated organised-crime syndicates; interfered with or suppressed criminal investigations; induced law enforcement leaders into criminal actions; and participated in intimidation, victimisation, or the removal of whistleblowers and honest officials. That’s hard enough, but the institutions include the South African Police Service (SAPS), National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), State Security Agency (SSA), the judiciary and the metropolitan police departments.

It's clear that the president was being pulled in different directions here. On the one hand, he wanted to underline the importance of the enquiry by setting its terms very wide. On the other hand, he doesn’t want it to last very long. But setting the parameters so wide makes it more than likely that we are looking at a long-term final report. This is not good.

- The one important thing omitted was clarity around the fate of the Political Killings Task Team (PKTT). It's not in dispute that Mchunu ordered the closure of the task team in December last year. What is in dispute is whether Mchunu actually had the power to close the unit. National Police Commissioner Fannie Masemola claims he never signed any official order to disband the unit, and insists that operations remain intact — though some case dockets were reportedly removed and archived elsewhere.

The University of Zululand’s professor of criminal justice, Professor Jean Steyn, has said the national police commissioner does in general have the authority to close down a police investigating unit. But the problem is that this was essentially a provincial unit, and according to the Police Service Act, that function is partly delegated to the provincial commissioner. Mkhwanazi said the minister had unilaterally shut down the unit without consultation with him, which might make it invalid. National Police Commissioner Fannie Masemola also claims he was not consulted.

Mkhwanazi says Deputy National Commissioner for Crime Detection Lieutenant General Shadrack Sibiya was the one who actually did the closing, though Sibiya has publicly stated he acted according to the instructions of Masemola. But Masemola now denies this.

And about those dockets. According to Mkhwanazi, Commissioner Sibiya took control of about 121 case dockets that the unit was working on by subsequently transferring them to his office in Pretoria, where they have since remained untouched, he says.

The least Ramaphosa could have done is order the immediate re-establishment of the unit, especially since there are some cases that are part of an ongoing criminal investigation.

- The biggest problem for Ramaphosa is personal. His very explicit and primary mandate as president was to re-establish the rule of law in a country plagued by “state capture”. This was his signature promise.

Until now, there has been muttering about the length of the time it's taken to bring state capture cases, allegations of deliberate slow-footedness and so on. But now all of that is dramatically and emphatically confirmed.

As my colleague Shirley de Villiers points out, the case that obviously pushed Mkhwanazi over the edge was that a company run by Vusimusi “Cat” Matlala scored a R360-million tender (for which it was notionally unqualified) to provide health services to the police. This happened even though Matlala was already being investigated by the Hawks for other state tender irregularities, including the notorious corruption at Tembisa Hospital.

This all comes exactly and precisely out of the State Capture handbook: a ridiculously overpriced tender given to an obviously dodgy company, followed by an elaborate cover-up. As SA citizens and opposition political parties now disparagingly ask: “Has nothing changed”?

And if they have not, Ramaphosa’s signature promise goes down in flames. It's a sad epitaph for a presidency that showed so much promise.

Now, back to the last, and very speculative, good thing.

- This crisis might just save the Government of National Unity at least for a while.

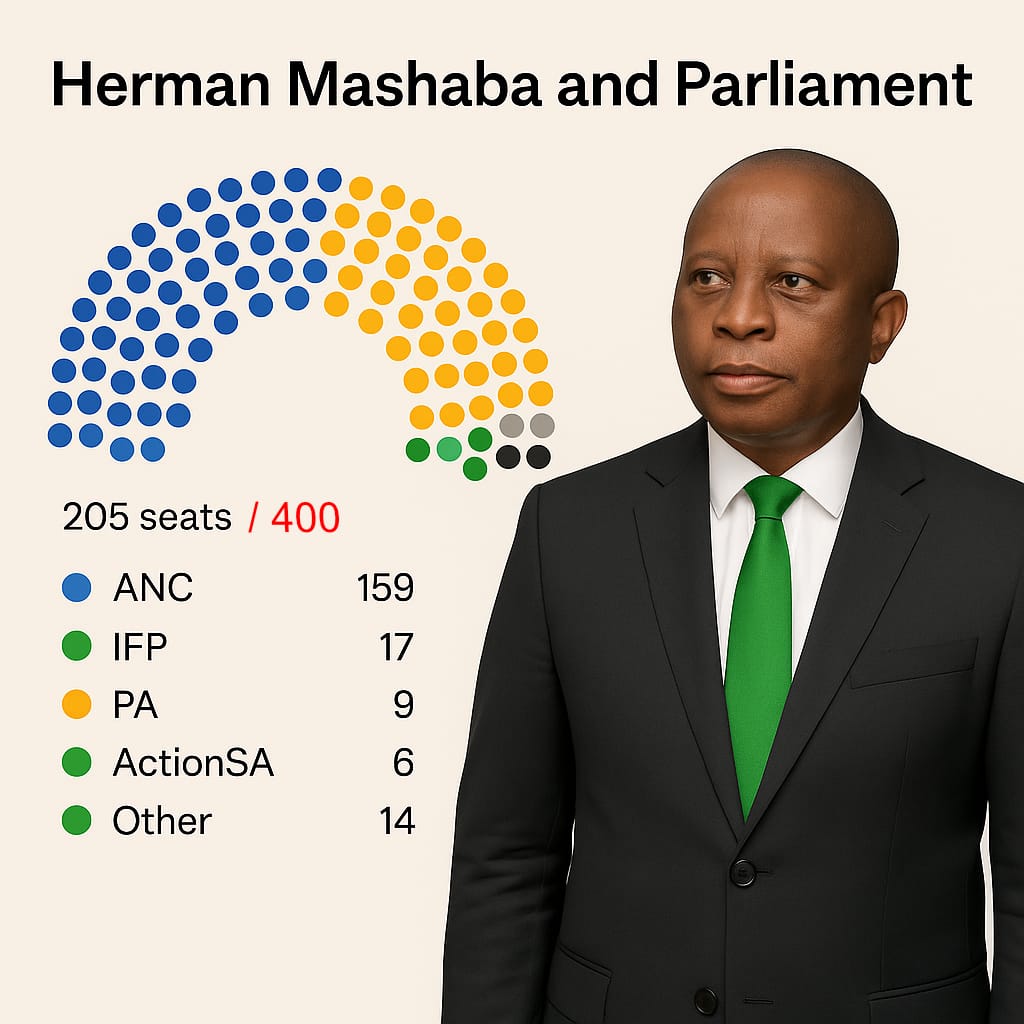

The ANC meets this week to discuss the future of the GNU, which is basically code for kicking the Democratic Alliance out and substituting them with six seats of Herman Mashaba’s ActionSA. It would be a tricky manoeuvre; the ANC would need every single small party and ActionSA, and even then it would have only a five-seat majority. Without ActionSA, it would not be possible. So ... tricky.

But this decision is now complicated because if the ANC tosses the DA now - the party of law and order - it will be handing them a fabulous political gift. As it stands, as a member of the Government of National Unity, the DA is technically responsible in part for this mess - or at least that is how the EFF and MK will argue the situation.

In some limited way, having the DA as a member of the GNU might actually mitigate some of the negative fallout from the scandal by preventing the DA from going hell-for-leather down this road.

The events also make it difficult for Mashaba to accept the ANC’s overtures. Won’t joining a party responsible for closing an investigative unit charged with preventing political assassinations be political suicide for ActionSA? I suspect it will.

Obviously, the parties might not see it this way, but it should at least be clear to the ANC that this is not the time to add salt to the wound and collapse the GNU, at least not yet. 💥

From the department of being really spaced out ...

From the department of the revolution that will be spotified ...

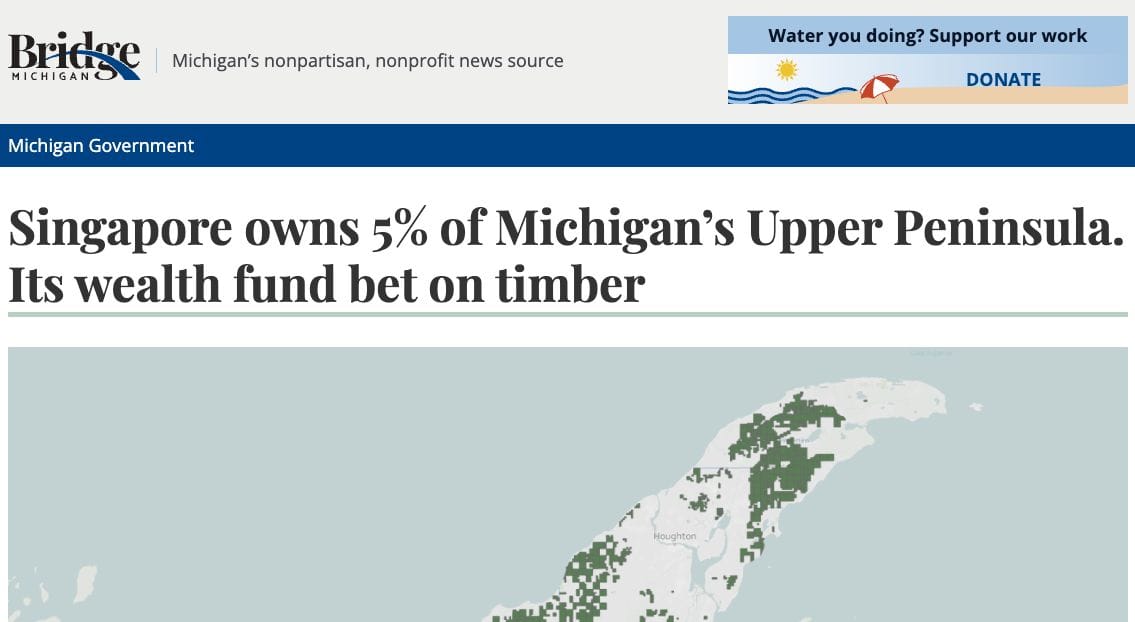

From the department of would you own it if you could...

Thanks for reading - please do share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation