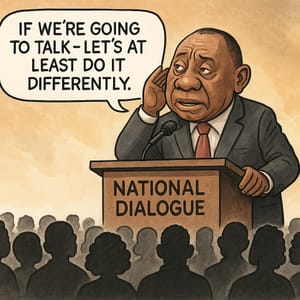

If Cyril Ramaphosa’s presidency had a sound, it would be the echo of a room full of clever people talking past one another. Ramaphosa has spent years calling for summits, dialogues, imbizos, legoktlas, and conventions — and yet South Africa seems no closer to resolving the basic crises that define daily life: crumbling infrastructure, soaring joblessness, state dysfunction, and public distrust.

This past week, the president returned to familiar form, announcing the launch of a new “national dialogue” — a society-wide conversation that will (eventually) culminate in a “national convention” next year, maybe. This is ostensibly meant to help South Africans “reimagine their future” and articulate “a common vision.” In the meantime, potholes deepen, public services hollow out, and South Africa seems to just amble on while the world overtakes it.

The intention behind the initiative may be sincere. It may be sincere - and political! But the public mood is not one of reflection. The overwhelming feeling is exhaustion. And instead of offering real political momentum, this dialogue has all the hallmarks of a presidency running out of ideas — but not words. Another big tent. Another panel. Another steering committee.

It’s not that dialogue is a bad thing. But talk without consequence, structure, or authority has become the defining vice of this administration. And South Africans know it.

The list of 31 people includes some great names not usually associated with functions like this: Robbie Brozin, entrepreneur and businessperson; Dr Imtiaz Sooliman, founder of Gift of the Givers; Siyabulela Xuza, award-winning rocket scientist; and Siya Kolisi, Springbok captain and world champion. These and others are interesting choices. It’s a genuinely imaginative list.

But the problem is that it also contains two explicitly ANC-aligned political figures: Manne Dipico, former Premier of the Northern Cape under the ANC, and Nompendulo Mkhatshwa, a former ANC MP and activist. There are also five others (including two of the three businesspeople!) who could be described as within the ANC’s broader orbit.

These include Bheki Ntshalintshali, former COSATU General Secretary; Brigalia Bam, former Independent Electoral Commission chair; Barbara Masekela, who once worked for the ANC and served as South Africa’s ambassador to the US; and the ANC-aligned businesspeople: former Anglo American director Bobby Godsell and Wiphold chair Gloria Serobe. You would never describe them as ANC card carrying members, but I think they would regard themselves as ANC-adjacent.

It’s true there are two definitively non-ANC-aligned politicians or former politicians: Roelf Meyer, former National Party minister and constitutional negotiator; and Lindiwe Mazibuko, former DA MP and parliamentary leader. But there is notably no-one who is even vaguely in the EFF or MK orbit. And neither is there is anybody in the group who has I would regard as a progressive economic outlook: this is a group of true-blue social democrats.

Then there’s a cluster of oddities: Lorato Trok, a children’s book writer; Sibusiso Vilane, a mountaineer and adventurer; and Mia le Roux, Miss South Africa 2024, who is also deaf — a choice that neatly ticks the “persons with disabilities” box. So, no — this is not quite the ANC-front the EFF claims. But neither is it wholly removed from, let’s call it current South African orthodoxy.

Three Big Problems

The three big problems, to my mind, are these:

- Political Timing: Given that the ANC appears to be losing its grip on the centre, proposing this initiative now aligns a little too conveniently with its electoral needs. That undermines its legitimacy.

- The Mandate: The dialogue is supposed “to confront our challenges and forge a path into the future.” How much looser can a mandate get?

- The Timeline: The plan is to come back next year with a programme of action. It’s so lethargic, it just reinforces national frustration with endless talking and minimal urgency and implementation.

Take just one issue. My guess is that what citizens really want — and what the ANC and perhaps some other parties really don’t — is to see corrupt politicians modelling their fetching orange uniforms. But given this initiative’s formation, structure, makeup, and vague mandate, there’s simply no way it will come close to addressing that issue with any vigour. The absence of SA's most popular Public Protector Thuli Madonsela is noticeable.

A Different Suggestion

Here’s a different idea — still grounded in dialogue, but done differently.

Let’s abandon the ritual choreography of ANC-led “national conversations” and borrow an idea with growing international credibility: the citizens’ assembly.

A citizens’ assembly is simple in concept, radical in implication. It involves selecting a representative group of citizens — at random, through stratified sortition — and asking them to deliberate on a major policy question. Participants are given access to expert input (of their choice), balanced briefing materials, and time to reflect and debate, often with professional facilitators guiding the process.

Unlike many of Ramaphosa’s dialogues — where the eminent are asked to pretend they speak for the ordinary — a citizens’ assembly reflects the real diversity of a nation: nurses and students, retirees and shopkeepers, informal workers and young graduates, not just bishops and brand ambassadors.

Importantly, the process is not just expressive, it is deliberative. People are not there to rant or posture for the camera. They are there to think. And when ordinary citizens are trusted with evidence, complexity, and time, they tend to do something remarkable: they produce better, more nuanced, and often more generous conclusions than politicians do.

This idea isn’t new. Ireland has used citizens’ assemblies to tackle constitutional reform, abortion, and climate change. The UK has tested them on electoral reform and net-zero targets. Belgium has integrated one into its Parliament. France’s Convention on Climate brought 150 randomly selected citizens into national policymaking — with serious, enforceable outcomes.

And yet, in South Africa, “consultation” remains a carefully managed theatre. Our public dialogues are often:

- Politically convened (by the same parties people have lost faith in),

- Over-scripted (with pre-determined terms and token stakeholders), and

- Chronically unaccountable (generating thousands of pages of reports, and zero action).

The contrast between a citizens’ assembly (sometimes called a "mini-public") and what is currently being proposed is stark. Citizens’ assemblies are:

- Randomly selected to ensure demographic and ideological diversity,

- Expert-briefed, with balanced input,

- Deliberative over days or weeks, and

- Focused on a specific topic — not a vague national reawakening.

The random nature of the selection process gets you away from the idea that solutions are always stitched into the existing political fabric. And unlike online arguments or parliamentary point-scoring, these forums encourage listening, not shouting. Participants are often surprised to find how much common ground exists — even on hot-button issues.

Crucially, they represent the quiet majority, not just the loudest voices. That gives them moral legitimacy and credibility, something in short supply in South African politics right now.

Missed Opportunity

What’s most frustrating is that this moment could have been different. Coming out of the 2024 election, South Africa had a chance to rethink not only who governs, but how we govern. Instead of using this transition to empower citizens, Ramaphosa defaulted to the most tired impulse of his presidency: the ceremonial conference.

Worse, it risks making South Africans feel that their voices only matter when filtered through elites — or when spoken in expensive hotels. In that light, this dialogue is not just slow. It’s profoundly alienating.

Ramaphosa often says that “dialogue is part of our national DNA.” Maybe. But this is not 1990. South Africans are not asking for another Codesa-style negotiation. They’re asking: How do I get a job? A working train? A police officer who shows up? A government that keeps the lights on?

A citizens’ assembly won’t fix the state. But it would do something essential: it would show that trust in democracy flows both ways. Not only must people trust the government, government must trust the people.

If Ramaphosa truly wants a national conversation, he should let the country speak — not through proxies and panels, but directly. And then, he must do what his critics say he never does:

Act on what he hears. 💥

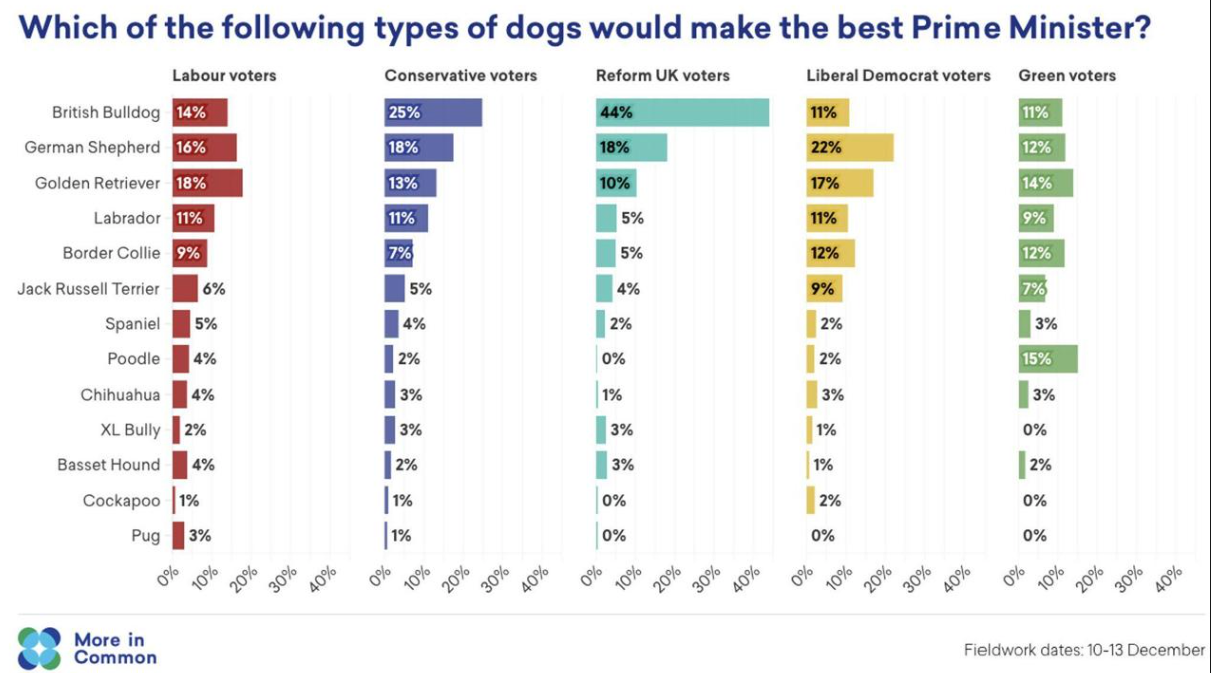

From the department of things not entirely unsurprising ..

From the department of loving those organic compounds ..

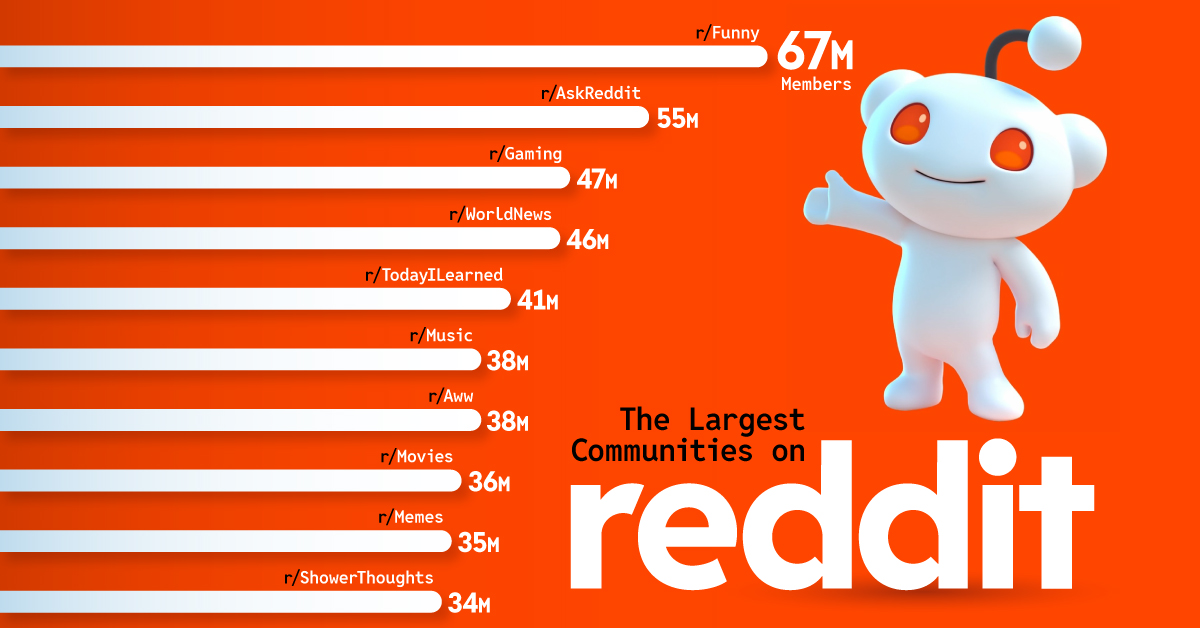

From the department of it being a dogs life (for the head of state!)

From the department the entirely expected and predictable: AI is making us less creative - already!

Thanks for reading - please do share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

Till next time. 💥

💥 💥 💥

Join the conversation