There is a really funny part of one of the world’s most enduring film oddities, Withnail and I. The movie is about two friends who are trying to become actors and living in a squalid Camden flat in 1960s London. They escape their crazy, drug- and alcohol-addled circumstances to visit Uncle Monty’s cottage in the Lake District, where things spiral into the weird, drunken, and hilarious.

On the way back, Withnail (Richard E. Grant) and “I”/Marwood (Paul McGann) are driving at speed in Withnail’s battered Jaguar, hurtling down the motorway in a state of hungover bravado. Withnail is again drunk (of course), imperious, and convinced of his own racing prowess; Marwood is terrified.

At one point, as the car veers through traffic and rain, Withnail declares with grandiosity, “I’m making time!”, meaning he’s driving fast, making good progress. The line is funny because it’s such a pompous, theatrical phrase - vintage Withnail - and because it completely misses the reality of the situation: he’s out of control, endangering them both. Marwood’s anxious silence and obvious terror heighten the absurdity.

It’s emblematic of the film’s tone - the mixture of doomed romanticism and ridiculous self-delusion. That little phrase, “I’m making time,” captures his tragicomic grandeur: the conviction of importance and success in the midst of chaos.

The scene also sets up the film’s deeper melancholy. For all Withnail’s theatrical bluster, we sense that time is the one thing he isn’t making - it’s slipping past him, toward an inevitable decline. The phrase, in retrospect, becomes almost ironic poetry: Withnail’s attempt to outrun the inertia of his life, to speed toward some imagined significance.

It's a bit like the process of “making” jobs.

For over three decades, the government of South Africa and society in general have all agreed that the most important development tool, the absolute quintessence of progress, is jobs. Jobs, jobs, jobs, said one ANC election poster. The desire to make jobs, or create jobs, or increase employment, whatever you want to call it, is hard-wired into the body politic for obvious reasons; unemployment is high and poverty widespread.

But guess what: no jobs.

In a sense, that is a very harsh assessment. Proportionately, SA's employment ratio has decreased. A lot of jobs have been created, just not enough to reduce unemployment proportionately speaking. In 1994, roughly 8.9 million people were employed. By 2024, that figure had grown to about 16.7 million (Stats SA QLFS, Q2 2024). So, in raw numbers, South Africa has added around 7–8 million jobs over 30 years.

But over the same period, the labour force more than doubled, from about 12 million to 25–26 million people. This means that even though millions of jobs were created, many more people entered the job market, resulting in persistently high and rising unemployment. In 1994, unemployment by the broad definition was around 20%; it's now around 33%. I mean, this is not good, especially when your explicit priority goal is to create jobs.

One of the problems is that it's actually very hard to “make” jobs, and we know this because there are two organisations, roughly the same size, using roughly the same methodology, that are trying to make jobs, and comparing them is enormously illustrative. The two organisations are the State-owned and run National Empowerment Forum (NEF) and the business development organisation associated with the Remgro group, Business Partners.

The first thing to say about both of them is that they are enormously valuable, successful, and resilient organisations. Business Partners started its life as a government-business joint venture called the Small Business Development Corporation (SBDC); it was initiated by Anton Rupert and Sanlam, in partnership with the then Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) and government.

In 1998, the SBDC was rebranded as Business Partners Limited and became a private-sector mid-market SME financier, focusing on deals of R500,000 to R50 million. It's now entirely self-funded and jointly owned by Remgro, Sanlam, and a variety of pension funds.

The NEF operates in a similar space, except it's focused exclusively on black economic empowerment, and it is state-funded: it got R2.5-billion from the Department of Trade and Industry (the dti) in the early 2000s and has not had to be recapitalised since.

As a state organisation, the remarkable thing about the NEF is how few scandals have been associated with its efforts. Sorry to be cynical, but let's be honest here. The NEF has managed to avoid the path of the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), which has made a whole bunch of huge, transparently ludicrous investments, many so dubious they can only be regarded as fraud. The closest the NEF came to being controversial was investing R34-million in the Hyde Park retail store Luminance, the vehicle of television personality Khanyi Dhlomo, way back in 2012. But this loan was paid back in full. There have been other failures; clothing manufacturer Delswa was closed in 2018; electrical manufacturing firm Surgeteck and wholesale/retail group Goseame both went toes up.

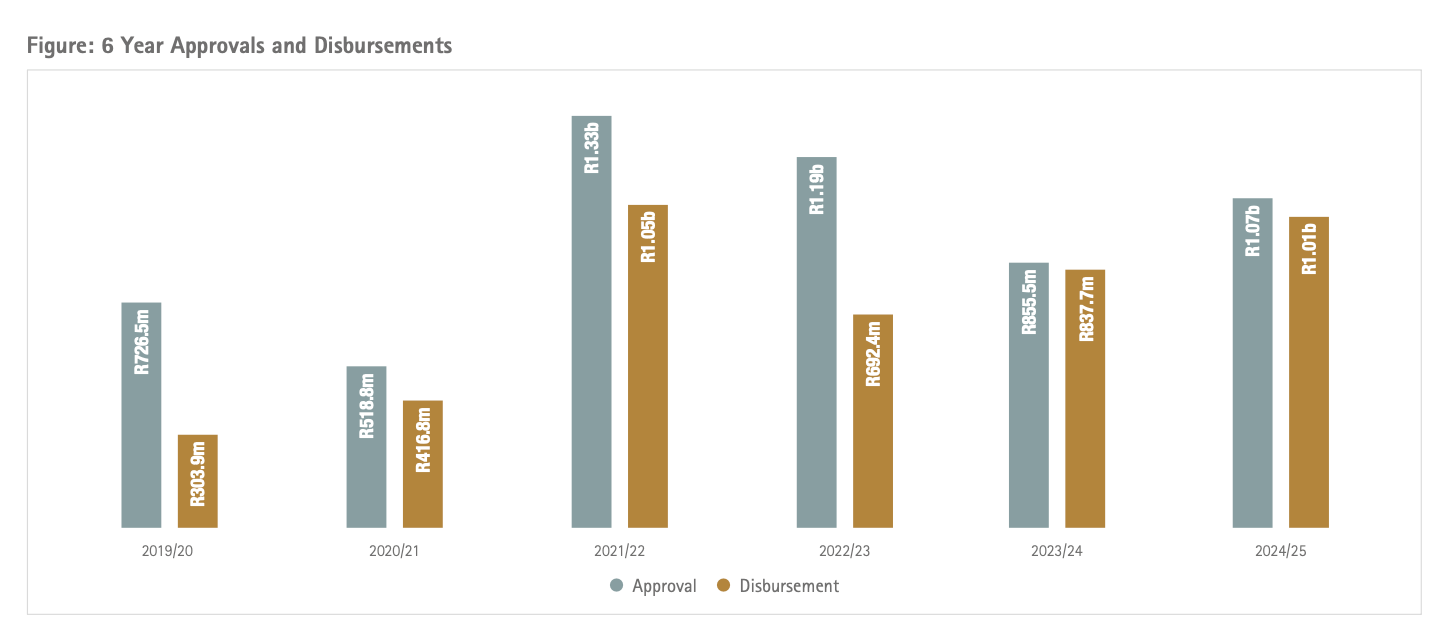

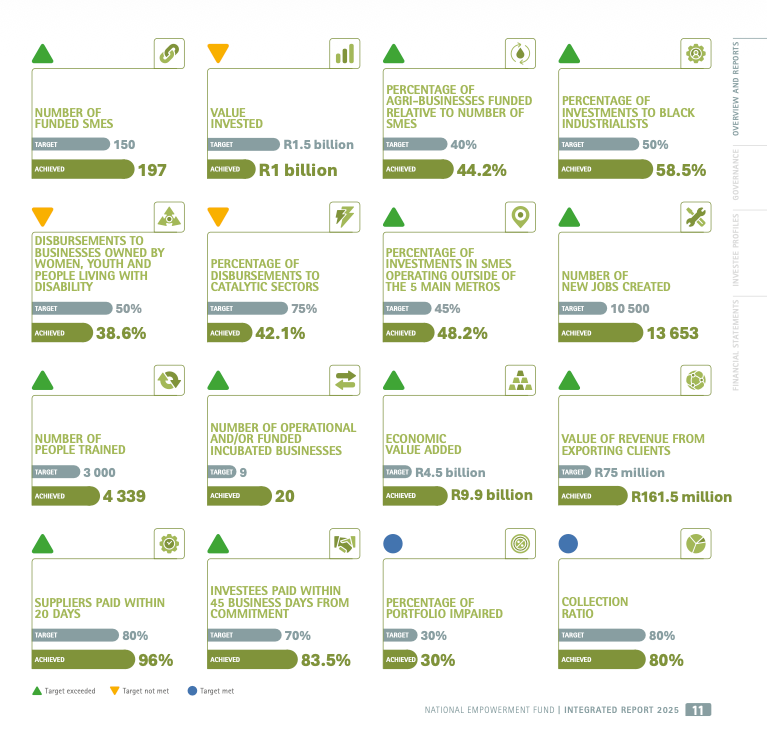

But, you know, be fair, making jobs is hard. And the NEF can claim some positives: its latest annual report, for example, boasts an 80% repayment rate, and it disburses about a billion rand a year. When it disburses loans at that rate, it “supports” around 14,000 jobs a year, as it did in 2024/25.

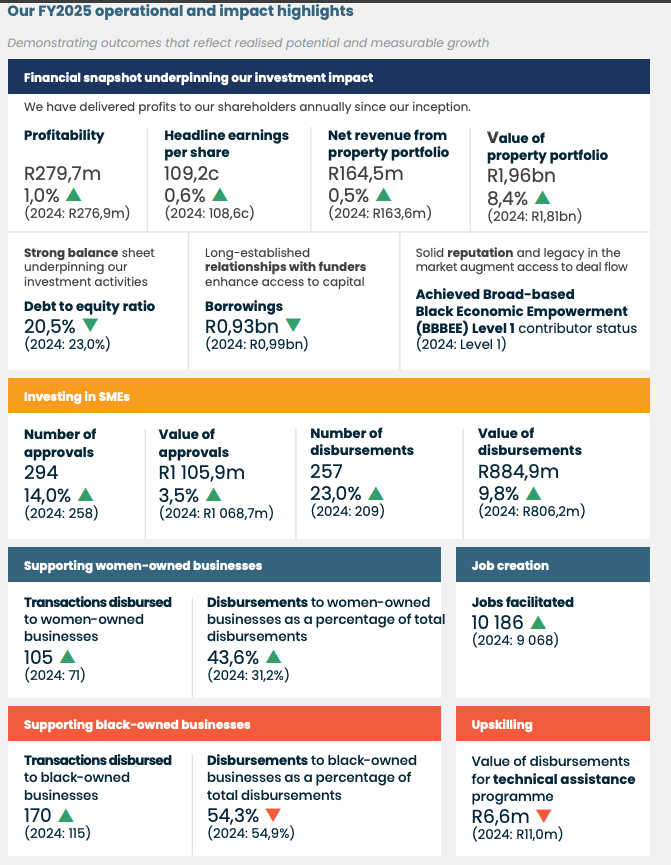

Compare this to Business Partners. Its 2025 report specified that it made loans of R884.9 million disbursed to 10,186 entrepreneurs. So, they compare favourably.

The biggest difference between the two is that the NEF’s loan book is, by design, a high-wire act: it clocks a gobsmacking 30 per cent impairment ratio and a non-performing loan rate around 27%. Still, it declared a return on investment of 9.5 per cent in 2024/25, which is impressive - perhaps even improbable - until one reads the fine print and realises that it includes fair-value revaluations and non-cash surpluses.

But it is also, in a perverse way, exactly the kind of risk-taking the state should be doing: lending where commercial banks fear to tread, where collateral is a distant dream and risk models sputter into incoherence.

Business Partners, on the other hand, plays at the opposite end of the spectrum: the pragmatic, actuarial world of expected credit losses (ECL), which in its latest year sat at 12.1 per cent, was less than half the NEF’s impairment level. Its return on equity hovers around 6.2 per cent, and its return on capital employed (ROCE) was around 8.9 per cent; modest, certainly, but stable, predictable, bankable.

What Business Partners gives you is the comfort of a clean balance sheet. What the NEF offers is a kind of messy, moral heroism: inefficient, bureaucratic, but born of conviction.

In the accounting of development finance, the true metric is not profit but jobs per rand invested. On that front, the latest numbers tell an intriguing tale: the NEF generated roughly 13.5 jobs per R1 million invested — a cost of about R 73 976 per job — while Business Partners managed 11.5 jobs per R1 million, at roughly R 86 874 per job. The NEF performed better here, but in previous years, the statistics have been inverted.

What intrigues me is how similar they are, and that it costs an enormous amount of money to "make" jobs. And of course, one must be careful with such metrics. A “job supported” can mean anything from a full-time salaried position to a part-time gig retained under duress. Both entities know this, and both report accordingly. But directionally, the NEF’s numbers show that public money, when disciplined but daring, can still move the needle.

What about the black economic empowerment angle? The dti is explicitly trying to create “black industrialists”; its loan book is focused on manufacturing businesses mostly in Gauteng and KZN. It proudly quotes that 58.5% of its loans were issued to black industrialists.

I don’t know what it means when it says this (I asked, the organisation didn’t reply): it only loans to black South Africans, and I presume it's pointing to its investment in industry, as opposed to those silly sectors like tech or tourism. Business Partners, by contrast, sees itself as market-based, colour-blind in theory, though not in outcome. In 2025, it disbursed 54.3 per cent of loans to black-owned firms and achieved Level 1 B-BBEE status, not because the law demanded it, but because the market increasingly rewards it.

There are two important points to be made here. The first is that development finance, at its truest, is not supposed to make money; it’s supposed to make markets. It is supposed to fill the gaps that the private sector cannot see or cannot justify.

Yet, the dti’s ideological focus on manufacturing means it's really not making new markets in new business areas so much as trying to develop businesses to compete with existing businesses. If it manages to do so, well, great. But is that development finance, as such?

The second thing is that both interventions are actually extremely small; the total existing SME funding by all financial institutions currently runs at around R300- to R600-billion, depending on your metrics. So even their combined disbursements — roughly R2 billion a year — barely graze the surface of South Africa’s SME financing gap, estimated at over R350-billion. Both organisations are making roughly 100 investments a year, and yet, there are 3.4 million small and medium enterprises in SA.

If you were being generous, you might say the NEF lends to correct the past and Business Partners to sustain the present. Both, if South Africa is lucky, might just help build a future in which race no longer dictates who gets to borrow, and who merely gets to hope.

If you are not being generous, you would say development finance on its own is a laudatory but insufficient force; to “make jobs”, the priority is to create a business-friendly environment for everyone's enterprises to grow and hire people. And a quick glance at business and consumer confidence figures shows that is where the real urgent work needs to be done.

For paid subscribers, I just want to pick up on the issue of development finance and race. To read this bit, please do consider subscribing - it costs the same as a cappuccino and it's much, much worse for your mental state, so great for

masochists!