Every year, the dictionaries gather like anxious clerics at a linguistic synod and attempt the impossible task of summarising twelve months of human behaviour with a single word.

The annual ritual of dictionary publishers anointing their Word-of-the-Year has become something of a linguistic beauty pageant, a contest in which neologisms and rediscovered archaisms parade before us in evening wear, hoping to capture the zeitgeist while the zeitgeist is still, technically speaking, geisty. It is an act of heroic compression: the reduction of a year’s worth of human folly into something roughly equivalent to Scrabble tiles. And yet we persist because words matter. Also,we enjoy arguing about them.

The words of the year for 2025 were, taken together, a kind of accidental confession. Not of who we think we are, but of what we spend far too much time staring at, clicking on, reacting to, or pretending not to enjoy while enjoying it immensely.

Take rage bait, Oxford’s choice, which is less a word than a diagnosis. Rage bait is what happens when the internet discovers that anger has a higher calorific value than joy, and infinitely more shelf life. It is outrage as product, or fury as a subscription model ('engragement is engagement' has been a mantra for newspapers for years). The phrase itself is almost too neat, like a behavioural science experiment disguised as entertainment. One linguist described it as “the monetisation of indignation”, which is academic code for we’ve all been played and we know it. And to make it worse, we actually like it - well, some people anyway. Comedian John Oliver, ever the dissector of societal absurdities, lampooned it on his show: "Rage bait? That's just what we call 'news' now - click here to get angry about something you can't change!"

Then there is slop, Merriam-Webster’s grimly accurate contribution, or AI Slop from Maquarrie Dictionary, which sounds like something you hose off a slaughterhouse floor, but in 2025 came to mean the endless grey porridge of AI-generated content now ladled into our feeds. Slop is not offensive because it is wrong, but because it is almost right, which is far worse. George Orwell warned us that vague language enables bad thinking; slop is vague language on an industrial scale. One wit remarked that AI slop is “what happens when plagiarism gets bored of being clever”. Short word. Ugly word. Perfect.

Parasocial, chosen by Cambridge, has been with us for decades, but is like an old friend who suddenly becomes relevant again when they start a podcast. It describes relationships that are intimate, emotional, heartfelt, and entirely one-sided. You know everything about them. They know nothing about you. Politicians adore parasociality. So do influencers. So do chatbots, which is where it gets unsettling. Linguist Steven Pinker, with his trademark cerebral wit, observed, "Parasocial bonds are evolution's cruel joke on the social brain— we've upgraded from stalking mammoths to stalking memes." Ha.

A linguist dryly noted that parasocial relationships used to be with television presenters; now they’re with algorithms that apologise when you’re sad. Progress, apparently.

And then there is 6-7 — or 67 — Dictionary.com’s choice, which is not a word at all, but a shrug disguised as a number. It means nothing and everything. It is used to signal agreement, dismissal, irony, boredom, solidarity, or the fact that one’s phone battery is at 3% and one cannot be bothered. If previous generations had “whatever”, this one has arithmetic. One classicist sighed that civilisation peaked when numbers were used for counting sheep. A stand-up comic called it “the sound a generation makes when it has run out of vowels”.

South Africa’s own contribution, valid, chosen by the SouthAfrica Language Board (PanSALB) is actually rather charming. It is the linguistic equivalent of a nod across a crowded room. It means: I see you. I accept your premise. I will not fight you today. In a country that specialises in argument, that’s no small achievement.

Taken togeather, 2025’s linguistic landscape was shaped strongly by digital culture and AI trends — with terms like slop, rage bait, and 6-7/67 echoing the year’s obsession with internet dynamics, generative content quality, and meme-driven communication. Other picks like parasocial show how language tracks evolving human-media relationships.

But words of the year are as interesting for what they exclude as for what they anoint.

For all these chosen darlings, the rejects sting like overlooked Oscar nominees. "Brain rot," that vivid indictment of mind-numbing scrollathons, was shortlisted everywhere but won nowhere—perhaps too on-the-nose for a year of cognitive decay. "Broligarchy," the bro-dominated elite, captured tech's testosterone-fueled takeover but was snubbed, maybe for being too pointed at Musk et al. John Oliver again: "Broligarchy? That's Congress with protein shakes."

How, for instance, did tariff not make the cut, a word that in 2025 bounced back into public life like an unwanted sequel, dragging trade wars, election slogans and economic illiteracy behind it? Or pivot, which has been stretched so thin by consultants that it now means “we have no idea what we’re doing, but we’re changing the slide deck anyway”.

Then there is resilience, which should have been retired on compassionate grounds. Once a noble concept, it is now deployed mainly to tell people to endure things that should not be endured at all. “Be resilient,” say institutions, meaning: please absorb this shock quietly.

And surely enshittification — the slow, deliberate degradation of everything that was once useful — deserved a late surge? Comedian Sarah Silverman noted that "enshittification is the only economic theory that makes sense anymore, assuming you're drunk enough." One scholar described it as “entropy with a pricing strategy”. Another simply asked, “Have you used the internet lately?”

There were also words that should have been chosen, had the dictionaries been braver.

Maintenance, for example, the unfashionable twin of innovation, without which nothing actually works. Or boring, which in 2025 quietly re-emerged as a compliment, particularly in economics and politics, where boring increasingly means competent, solvent, and unlikely to set the place on fire.

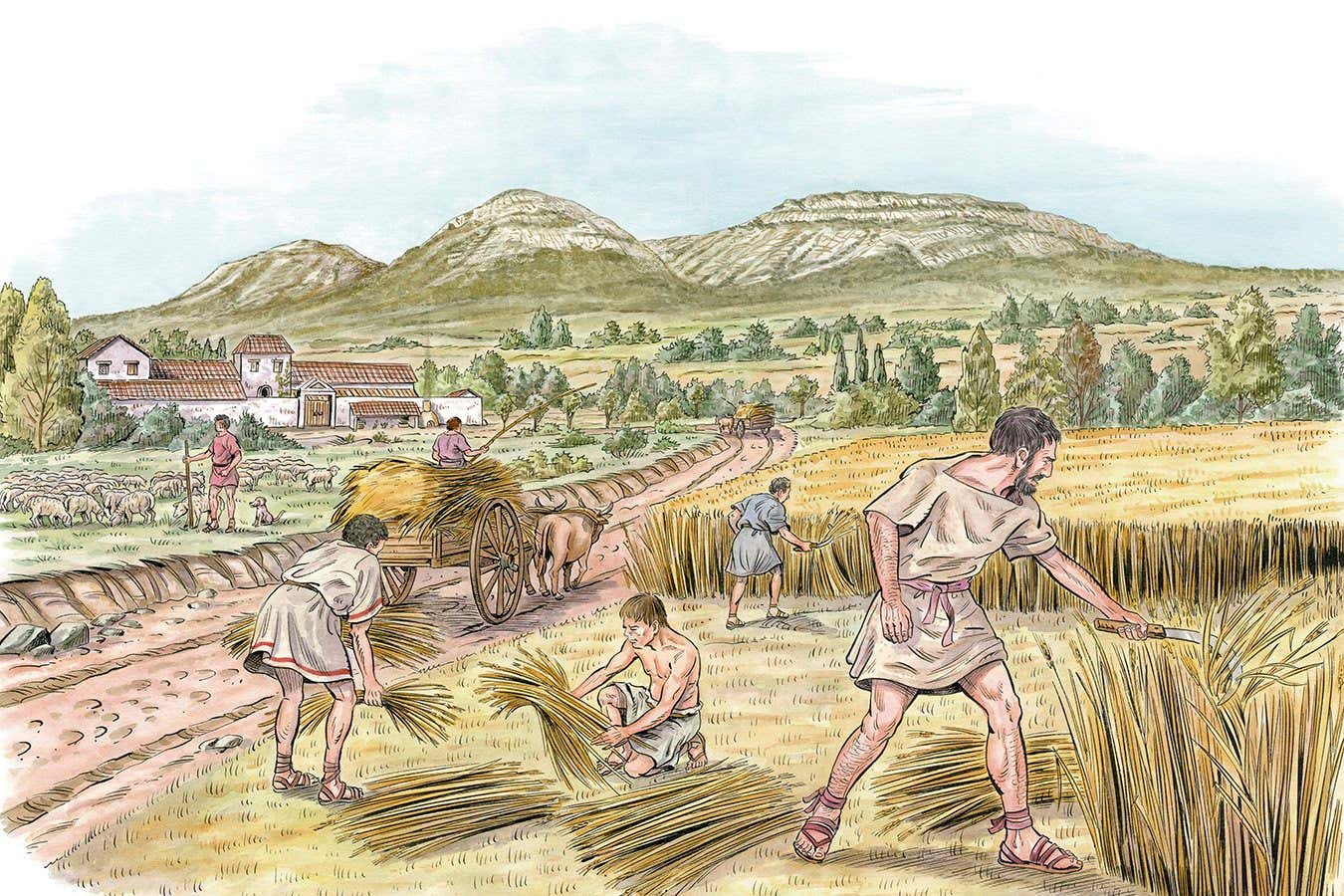

In his substack, Stellenbosch economics lecturer Johan Fourie creatively chooses three words of 2025, saying it will be a“BAD year”: Bees, Acacia trees, and Donkeys. Together, they describe how technology, geopolitics, and work are reshaping the world, especially for South Africa and other energy-poor or volatile regions.

- Bees (Energy and batteries):

Cheap battery storage is the quiet revolution of the decade. Like a bee colony, future energy systems will be distributed, adaptive, and resilient (nudge nuge) rather than centralised and fragile. Falling battery costs will matter enormously for Africa, enabling local storage, solar pairing, electric transport, drones, and new industrial organisation. By 2026, batteries won’t just cut costs—they will change how firms, households, and cities function in unreliable energy environments. - Acacia trees (Geopolitics and resilience):

The global order is becoming harsher and more confrontational, not just multipolar. Rising wars, defence spending, and blunt power politics favour resilience over cooperation. The acacia tree symbolises systems that survive in hostile conditions by conserving resources and defending themselves—but often grow slowly. For South Africa, 2026 could mark a cautious exit from a low-growth equilibrium if commodity demand holds and political institutions endure, not through dramatic reform but incremental root-deepening. - Donkeys (AI and work):

AI agents will increasingly take on “donkey work”—repetitive, time-consuming tasks—but also move into higher-level cognitive support: drafting, coding, researching, and decision-support.

Nice. My own nomination would be enough. Enough content. Enough outrage. Enough optimisation. Enough pretending that everything new is better simply because it is louder.

Still, the chosen words tell their own story. A year obsessed with anger, flooded with slop, emotionally entangled with strangers, communicating in numerical grunts, and occasionally offering one another a small mercy: valid.

Language, as ever, has not failed us. It has merely held up a mirror. And we, enraged, parasocial, scrolling knee-deep through slop, glanced at it briefly.

Then we refreshed the feed.

- 💥

The video version of my AI graphic - just for fun!

From the department of cows have guns ...

From the department of very, very unintended consequences ...

From the department of things that are totally predictable ...

From the department of the rather obvious dangers of kissing frogs ...

Thanks for reading - please share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

By all means, comment on the post - I'm interested in all feedback, good, bad, indifferent.

Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation