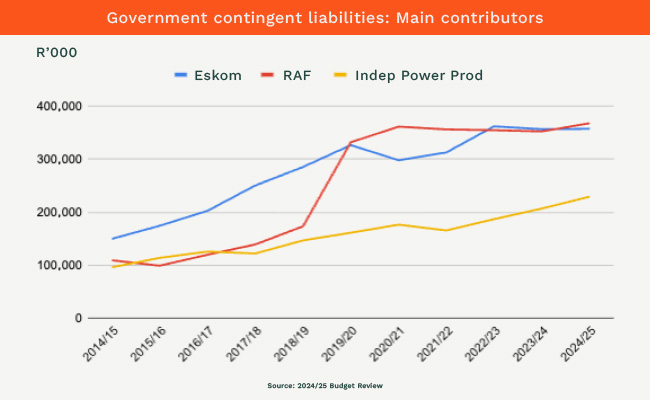

One of SA's biggest State disasters of the post-state capture period has also been one of its least noticed; the Road Accident Fund (RAF). The reasons are complex, but one way to measure them is to look at the government’s contingent liabilities - the potential debts that might drop onto the government balance sheet if certain conditions are satisfied - or not satisfied.

I would guess that if you asked informed South Africans what the biggest contingent liability is at the moment, the majority would punt for Eskom, and they wouldn’t be far wrong. But as it happens, the biggest contingent liability at the moment is, according to Treasury documents, the RAF.

It's absolutely chilling that an organisation this huge, with a R50-billion annual budget, can go this far wrong, this fast.

Unlike a normal government debt liability, which is generally an unconditional obligation to pay a specific amount at a defined time, contingent liabilities are uncertain. How uncertain, you ask? In the independent power producers case, they are not really uncertain at all because it's unlikely that Eskom won’t need or won’t be able to pay for the power they produce. In the RAF’s case, they are the very certain kind of uncertain.

So what is this all about? Here, we need a brief excursion into history. If you are involved in an accident that causes injury to a third party, in law, the "third party" has a financial claim against whoever caused the accident. The kinds of losses you can claim are enormous: damage to property, medical expenses, future medical care, loss of income, loss of earning capacity, pain and suffering, business interruption, and so on. It mounts up damn fast.

With the huge increase in motorised transport over the years, there has been a concomitant increase in car accidents globally because essentially, you are hurling about a ton of metal, glass, and plastic around the shop. If you collide with another ton of metal, or just intersect with a pedestrian, some painful stuff ensues, and not just of the personal variety. Around the world, the money involved in car accidents has just exploded. So in most countries, motorists are obliged to buy third-party insurance.

I remember as a kid my mom getting into terrible trouble for forgetting to buy a third-party insurance disc, which you had to do every year. The fine you had to pay for not displaying it was enormous; if you caused an accident and someone got injured, the total costs to you could be financially crippling. And this happened quite often.

So, during the apartheid era, someone came up with a new plan: nobody would have to buy third-party insurance; it would be automatic, and it would be paid for by a levy on the fuel price. Brilliant. Not.

The joy of the new system was that victims would never find themselves in the unenviable position of having to bankrupt someone because of an accident - or not be able to get anything at all if the responsible person was broke. Everybody would be automatically insured. Insurance companies that provided third-party insurance were a bit unhappy about the change, but the government at the time considered the benefits to outweigh the costs. The levy on the fuel price was then very small. I think it was about 1%, if memory serves. People forget how socialist the instincts of the apartheid government were.

Anyway, at the start, the system worked pretty well. All the claims were put into a pot and paid out every year. But soon, the wheels started to come off, because the incentive of the claimants is to claim as much as they can, and the political incentive of the government is to keep the petrol price as low as possible. It's a classic case of a government solution established with the best intentions gradually going wrong. And, oh lordy, has it ever gone wrong!

Over the years, the claim quantity and value massively increased, including legal fees and medical claims. Despite political pressure not to increase the petrol levy, increases were gradually introduced, and now it constitutes somewhere between 10 about 15% of the total cost of petrol. How on earth did that happen? This is what happens when governments start benefits programs; they just become unstoppable, runaway freight trains.

Anyway, to meet this problem, government initiated a commission back in 1999 to look at the situation under the auspices of Judge Kathy Satchwell. I love these commissions: while the downside is that they take years because I suspect the commissioners just love the cash flow, they often come up with thoughtful solutions. (After that amount of time, you would hope so.)

Of course, those solutions are never put into practice. That would defy the first law of government commissions: by all means make sensible recommendations and suggestions, but don’t expect any action to stop the people who are milking the system from, you know, milking the system, because they are going to make a terrible fuss.

As so it was in the case of the Satchwell Commission. The commission found (three years after it started looking) that the fault-based compensation (called the tort system) resulted in high administrative and legal costs and, consequently, the system was insufficient, inequitable, and unsustainable. All of this was naturally totally obvious at the time, and is more so now. But the commission's recommendation was to suggest a hybrid no-fault system, with limits and thresholds.

But the lawyers went nuts because in RAF cases, lawyers typically act on contingency, and these costs are very high to the victims. Often, 25% of the total payout goes to lawyers' fees. The idea that there should be thresholds, and worse, no party-on-party cost awards, would strip billions out of the payment system. They didn’t argue it that way, of course. The General Council of the Bar, for instance, warned at the time that replacing fault-based compensation with fixed benefits “might deny some victims the full compensation they deserve, and might be inherently unfair in some cases”. Right.

So the government went some way - but not all the way - toward putting the commission’s recommendations into practice, essentially by trying to extend the power of the fund to conclude agreements. The Road Accident Fund Amendment Act was introduced in 2005, certain terms were better defined and so on. Weirdly, rather than limiting the payouts, in some situations the amendments actually increased them!

What was most striking were not the changes, but the timidity of the changes. Oddly, the one thing the commission did not do was recommend the thing should have recommended: that the fund be scrapped, and third-party insurance should be outsourced to the private sector which would have a big, strong incentive to run it properly. It could even confined the fund to only cases where private sector third-party insurance was not available. Around the world, no-fault systems are gaining ground fast, because speed and simplicity are what accident victims need most, and cheap systems are what government's want most.

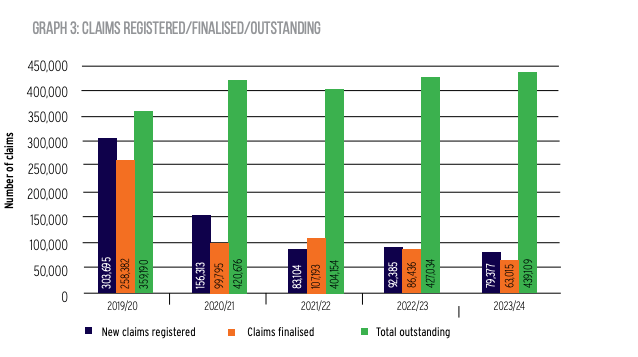

But anyway, life goes on in SA, with claims gradually mounting and because of its other failings (thieving, for instance) during the State Capture period, government started running out of money, and begin to resist increasing the RAF petrol levy. The Treasury’s position was that the RAF needed to operate within its budget, but that is easier said than done when you are facing mammoth and increasing claims. The crisis just got worse and worse.

So, to try to address this problem, the transport department, under then-minister Fikile Mbalula, who is now ANC Secretary General, decided to send in one of their heavy hitters, Collins Letsoalo, a veteran of different areas of the transport department and former departmental CFO. There was one problem, though: Letsoalo had recently been kicked out of the Passenger Rail Agency of SA for hiking his salary from about R1.3 million per year to R5.9 million and also demanding perks like a chauffeur-driven car and unlimited cellphone usage. The board, already under pressure because of the “tall trains” catastrophe, claimed the increase was not approved and booted him back to the Transport Department.

When Letsoalo got to the RAF in 2020, he was outraged at how much lawyers, particularly white lawyers, were getting paid, and he famously publicly named and shamed them, listed what the firms were getting paid. The numbers were and are extraordinary, but this is how the tort system works; it’s adversarial, and lawyers try to get the most they can for their clients - and try to negotiate the best deal they can with their clients. If lawyers are successful, they are going to get a lot of clients. And anyway, the complaint was a bit rich coming from Letsoalo, who had somehow managed to engineer his salary up to around R11.5-million a year at this point. But it gives you the measure of the man: haughty, bullying, self-important, self-righteous, all the good stuff in a manager of a failing organisation.

What Letsoalo could have done was try to improve efficiency at the RAF and get claims handled quickly. But instead, he tried to solve the system by cutting out the lawyers entirely. He started by scrapping the system of using external lawyers as settlement advisors, called the board system. That initially saved the RAF money, but ended up being a disaster because cases just weren't settled. So the lawyers, being lawyers, would apply for default judgment, thereby jamming the courts with RAF cases. And then the system just imploded because on top of existing costs, the RAF started having to pay huge interest charges. So, to try and fix the situation, the RAF instead did something nuts? It just stopped paying. Can you believe it? It just refused to pay foreigners, for example. This led to a sheriff's department lumbered with trying to wheedle cash out of the fund.

So, back to my whistleblower. As it happens, I got involved in this as a reporter when I noticed the RAF annual report had specified that the organisation had around R700-million in cash on its books. It struck me as odd that an organisation reputedly bankrupt had that much money available, and I innocently asked the organisation how this could be.

The response was massively hostile. They refused to answer. It went further. At a subsequent press briefing, Letsalo all kinds of other questions, but refused to answer any questions about the cash position of the RAF. Amid a whole bunch of racial smearing, he then accused “some journalists” of being paid agents of the lawyers - obviously referring to me.

It later occurred to me what the problem was. The RAF must have been hiding this money because if it didn’t, the sheriff would attach the accounts on behalf of claimants who had default judgments against them. So the RAF thought I was trying to help the lawyers by asking where the money was invested. In fact, I was just interested in a journalistic sense; I had unwittingly ambled into a bee's nest.

Well, then the whole thing started unravelling. At this point, a whole bunch (for lack of a better collective noun) of whistleblowers of one sort or another approached me and other journalists. Former RAF employees who had been ousted, people who hadn’t been paid, judges of the Supreme Court! It was just incredible. The quantity and variety of the people the RAF had managed to infuriate, double-cross, hoodwink, or oust under dubious circumstances was mind-boggling.

One told me about the new hiring policy of the RAF that included the right to overlook previous criminal charges. This was necessary because, in order to hide the money, the RAF had hired a fund manager who had been let go by his previous state employer, the City of Johannesburg, after it was discovered he had possibly fraudulently allocated money in a dodgy deal to a friendly finance house. Another whistleblower told me about two absolutely huge advertising contracts the RAF had signed, amounting to, in total, and I am not making this up, just under R1-billion. We will hear lots more about these soon.

One of the whistleblowers has been more significant than most - although all have played their part. His name is Kabelo Malao, and this is broadly his story, which has been partly reported in the press sporadically. He was actually an employee of the RAF for a stage, but then decided to try his hand at acting for accident victims. After speaking to Malao for some time now, what I know about him is that he is totally unstoppable; he is like a rhino. Over the years, he brought different sets of cases, some of which have been settled and some not. But there remains one set of cases involving 29 different victims - what he calls his "spreadsheet" - in which the total amount due according to Malao is now R25 400 000 with interest.

This set of claims is very contentious, and was responsible for a long and very confusing legal battle between him and the RAF that has been continuing for years, going backwards and forwards and touching on a variety of different issues, some of which I won’t mention here. But the real bitterness began in 2021 when Malao executed against the RAF, and the sheriff actually removed some office furniture from the offices of the Ministry of Transport. Bold move!

On the second day, the removals were supposed to continue, the sheriff was presented with an undertaking to pay by the then Director General of Transport Alec Moemi, which had the effect of halting the execution. At the time, Transport Minister Fikile Mbalula said he was furious about the surprise attachment of assets from the department's offices by the Sheriff of the Court.

Malao says that after he insisted on a proof of payment rather than just an undertaking to pay, the DG delivered the proof of payment, which had the effect of halting the execution. The amount involved at this point was just over R14-million. But the money was never delivered; it seems the payment was made and then reversed.

So Malao then pursued the matter in the courts, but at this stage, the RAF was in the habit of just ignoring court orders. Eventually, in 2023, Malao says he was paid the legal fees involved in this set of cases, which came to about R5-million, but not the capital amount. Malao then, of course, wanted to know whether this meant the balance would be paid.

As a previous employee, Malao knows how the computer system works and got access to a copy of the computer record of the payment. It turns out this record, which purports to suggest he had been paid, is abnormal in many respects. The RAF has refused to talk about specific cases, but it has acknowledged in the past that some payments have been historically diverted.

We know this because the Special Investigating Unit has been investigating various problems with the RAF, and this was one of the many issues involved. How did the SIU get involved? Well, presumably the same people talking to me now have been talking to the SIU for years; Malao has acknowledged he was one of them.

So my guess is this: the RAF knows Malao attached the Transport Department's furniture and got the SIU onto them and in a fit of pique, so it decided to withhold his claims. I could be wrong, but that’s what makes sense to me. But the crisis increased in intensity, because then some aspects of the SIU reports were made available to the Parliamentary Committee on Public Accounts, and as a result Letsoalo was suspended, and his contract has not been renewed. The entire board of the organisation has now been replaced.

But the problem is that all the existing employees of the RAF are mates of Letsoalo, and they apparently still refuse to pay Malao the capital amount due him, even after the RAF has undertaken to pay outstanding claims, and has paid many. I have now sent perhaps a dozen requests for information to the RAF over the past year on different topics, and the organisation has refused to answer a single one in full. Asked whether it intends to pay Malao, or whether it considers the amount outstanding, the organisation refuses to say or just doesn’t reply.

So Malao is still trying to get his clients' money. He even reported the three most senior members of the RAF to the commercial branch of the SAP, basically for the fraud involved when, according to him, they informed Malao in writing that he had been paid when he hadn’t. The police initially followed up the case, but after several failed arrest attempts, the case was referred to the NPA.

In the meantime, Malao said some of his clients, who include kids orphaned by the accidents, have now been waiting five years to get their payout. Malao recently sent me and other interested parties an open letter about his plight. It's pretty heartfelt. This is how it ends:

“I stand today as a broken man, a cautionary tale. I would never, ever be a whistleblower again, in South Africa or anywhere else in the world. The system is designed to consume those who speak truth to power. People in powerful positions use your information, they build their careers and convictions on the evidence you provide, and then they leave you in the cold to face the retaliation alone. We read of whistleblowers who are praised as heroes only after they are murdered. I am one of the "lucky" ones; I am still alive, but my professional life has been terminally assassinated.

"This is my formal complaint. It is a cry into the void, but it is one that must be recorded. The RAF is collapsing under the weight of corruption and maladministration that I warned against, perpetrated by the very individuals I named. A R400 billion debt stands as a monument to the ignorance of my warnings. My destroyed practice and my clients' 1800 days of unpaid claims are the human cost.

"My plea is no longer for myself—it is perhaps too late for me. My plea is for my clients. They do not deserve this punishment. They are not collateral damage in a political war; they are citizens entitled to what is lawfully theirs. I demand that the new leadership of the RAF, the Minister of Transport, and the SIU intervene immediately to ensure my clients are paid every cent they are owed, with interest, without further delay.

Until that happens, my story will remain a stark indictment of a nation that claims to cherish integrity but devours its guardians.

Signed,

A Broken Citizen,

A Ruined Professional,

A Reluctant Whistleblower”. 💥

From the department of stuff you actually don't really want to know ...

From the department of DNA - Don't Need Alcohol, or perhaps Do Not Ask ...

From the department of very noisy neighbours ...

Thanks for reading - please do share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation