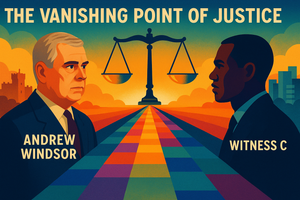

There is an odd connection between two of the big events of this past week: the evidence of Witness C at the Madlanga Commission and the stripping of the royal title of the person we all knew as Prince Andrew. “And what is that?” I hear you ask. Let me explain.

A whole concatenation of revelations at the Madlanga Commission over the past month has been explosive, but this past week they reached a crescendo. Witness C is a member of the disbanded Political Killings Task Team, and he was giving evidence in camera at the commission. He relayed information provided by murder accused Vusimuzi “Cat” Matlala, who was very, very disgruntled about how he was no longer being supported by people to whom he had paid bribes in the past – as you might expect.

One of the people on the receiving end of his bribes, he said, was the now-sidelined police minister, Senzo Mchunu, and he claimed to have paid R500,000 towards Mchunu’s campaign for the ANC presidency. That draws a direct line between tender corruption, the most senior members of the police and the political system. Even for us jaded journalists, that’s pretty shocking.

If only that were where it ended – but there was more. Witness C said Matlala had made regular cash drop-offs at the home of suspended SAPS Deputy National Commissioner of Crime Detection Shadrack Sibiya, providing Sibiya’s phone numbers, and details of the drop-offs. These took place at a traffic circle at a private Sandton residential estate, and the claimed drop-offs amounted to R1-million a month. They should check his couches.

Matlala also provided a whole bunch of one-off payments, according to the witness, including R2-million to buy a plot that contained 20 impalas. The animals have since died. Obvs. Matlala claimed Sibiya was “a criminal who loves money”. You don’t say. (Matlala, Mchunu, and Sibiya all deny the charges.)

So that is the one thing. The other thing is that the person formerly known as Prince Andrew has been stripped of his “prince” title and booted out of his house on the Windsor estate, the Royal Lodge, after weeks of intense scrutiny over his links to convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Mr Windsor gave up his other royal titles earlier this month, including the title of Duke of York, after the publication of a posthumous memoir by Virginia Giuffre.

Giuffre, who has taken her own life, claimed she had sex with the then-Prince Andrew on three separate occasions. But the cruncher is this: the memoir records Giuffre asking Windsor if he could guess how old she was. He guessed right: 17. She asked how he knew, and he creepily replied that she was just a bit older than his own daughter. Windsor has always claimed he did not have sex with that woman, to quote a phrase. But this revelation suggests he was probably committing statutory rape and more than that, he knew it at the time. (The age of consent in the UK is 16, but 18 for people in relationships of trust like teachers, trainers, and, one presumes, princes.)

To me, the connection between these cases has to do with the nature of justice. Justice has the irritating habit of disappearing just as you think you’ve caught sight of it. We talk about it constantly, invoke it in speeches, scrawl it on banners, engrave it above court doors. Yet when we reach out to touch it, our fingers close on air.

The problem, perhaps, is that justice lives in two realms at once. There’s the idea of justice – pure, eternal, radiant with reason – and then there’s the practice of justice, which involves people, paperwork and the odd misplaced affidavit. The ideal belongs to Plato; the paperwork, to Home Affairs. Somewhere between those two poles the signal gets lost.

Every generation believes it’s on the verge of finally fixing the justice question. We draft constitutions, hold inquiries, rename ministries, commission commissions of inquiry into commissions of inquiry – and still, the substance keeps slipping through our fingers. The truth is that justice, unlike power or wealth, doesn’t accumulate. It has to be remade, constantly, painfully, by fallible people trying to stand upright in the storm of their own interests.

Part of what makes justice so ephemeral is that it’s relational, not absolute. It only exists between people. What looks like justice to you may look like retribution to someone else. And there is another thing: justice is slow, but outrage is instant. The algorithm favours fury over fairness. In our world, justice is too often represented not in the formal justice system and the court but in virality. And yet, ironically, that speed only deepens the illusion of motion. We confuse circulation with progress.

That is what we are seeing now, in both these cases. It’s a kind of mirage of justice, or perhaps the potential for justice. And oddly, it’s more satisfying than it should be. 💰

First published in CurrencyNews. Subscribe to the free Currency newsletter here.

Join the conversation